Money is often treated as the ultimate solution to social problems. Campaigns stall without it, organisations chase it relentlessly, and many changemakers feel that without sufficient funding their work cannot move forward. Yet this assumption—that money itself is a resource—deserves closer scrutiny. When examined through systems thinking, economics, and social change theory, money looks less like a resource and more like something else entirely.

Reframing money is not about denying its usefulness. Rather, it is about understanding its true role so that it does not distort how we approach change, organise collectively, or imagine alternatives to the systems we live within.

Money as a Neutral Tool, Not a Moral Force

Money is often described as good or bad, corrupting or empowering. In reality, money itself is morally neutral. It does not carry ethical value on its own. Any moral significance attached to money comes from how it is generated, distributed, and used.

As a medium of exchange, money enables transactions. It facilitates movement between goods, services, labour, and resources, but it does not determine outcomes. The same unit of currency can fund extractive industries or regenerative projects, exploitation or care. The ethical dimension lies in human intention and structural context, not in money as an object.

Understanding money as neutral allows for more honest conversations. It moves discussions away from guilt, shame, or moral posturing and towards accountability, systems design, and collective priorities.

Why Money Is Not a Resource

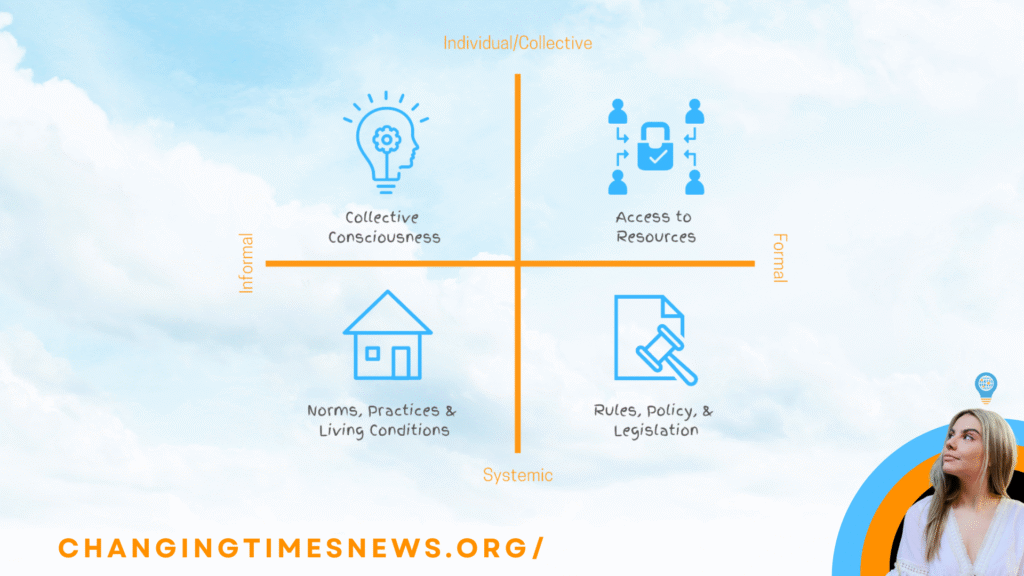

In social change and systems thinking, a resource is something that directly produces capacity or capability. Food nourishes bodies. Skills create competence. Relationships generate trust and coordination. Knowledge enables informed decision-making.

Money does none of these things on its own.

Instead, money functions as a currency—a mechanism that allows access to resources. It is the means through which resources are acquired, not the resource itself. Confusing money with resources often leads to shallow problem framing, where the absence of funding is treated as the core issue rather than a symptom of deeper structural constraints.

When changemakers say “we need money,” what they usually mean is that they need people, time, skills, infrastructure, legitimacy, or coordination. Money may help unlock those things, but it is not interchangeable with them.

Money as Energy Within Systems

A more accurate way to understand money is as a form of energy within a system. In physics, energy is the capacity to do work or produce change. In systems theory, energy refers to what flows, circulates, and activates processes.

Money behaves in a similar way. It moves through systems, accelerates action, amplifies existing structures, and enables exchange. Where money flows easily, activity intensifies. Where it is constrained, movement slows.

This framing helps explain why money alone cannot transform systems. Energy does not determine direction; it only fuels motion. If money enters a system designed around inequality, extraction, or accumulation, it will reinforce those dynamics. If it circulates within cooperative, regenerative, or community-led systems, it can strengthen those instead.

The problem, then, is not a lack of money, but the systems through which money flows.

The Myth of Noble Struggle

Within the social impact space, there is often an unspoken belief that financial struggle is virtuous. Scarcity becomes a badge of integrity, while stability or success can trigger discomfort or suspicion. This narrative, while emotionally powerful, is deeply limiting.

There is nothing inherently noble about choosing struggle when alternatives exist. Financial precarity does not make work more ethical, nor does abundance make it less so. In fact, chronic scarcity often reduces capacity, creativity, and sustainability, making long-term change harder to achieve.

Rejecting the myth of noble struggle allows changemakers to pursue financial stability without abandoning their values. It also opens space to ask more strategic questions about scale, collaboration, and collective resourcing.

Rethinking Wealth Beyond Money

One of the consequences of overvaluing money is that it narrows how wealth is understood. Wealth is often reduced to income, assets, or savings, despite the fact that wellbeing depends on far more than financial capital.

A more holistic understanding of wealth includes multiple forms of capital:

- Human capital, such as skills, experience, and knowledge

- Social capital, including relationships, trust, and networks

- Time, which shapes capacity and choice

- Physical assets, like land, tools, and infrastructure

- Cultural and intellectual capital, which influence meaning and legitimacy

When wealth is understood in this broader sense, the obsession with money begins to loosen. Communities often possess enormous wealth in non-monetary forms, even when financial resources are scarce. Recognising this allows for more creative, resilient, and collaborative approaches to change.

From Scarcity to Collective Enoughness

Scarcity is often experienced as an individual problem: not enough money, not enough time, not enough capacity. Yet many social change frameworks emphasise that scarcity largely emerges when people and organisations operate in isolation.

Collective approaches—networks, cooperatives, mutual aid, shared infrastructure—frequently reveal that there is enough when resources are pooled, coordinated, and distributed differently. This idea, sometimes described as collective enoughness, shifts focus from accumulation to alignment.

Money can support this process, but it cannot replace it. Without trust, relationships, and shared purpose, additional funding often fails to produce meaningful transformation.

Why This Shift Matters Now

At a time of economic uncertainty, political fragmentation, and widespread distrust in institutions, rethinking money is not an abstract exercise. It directly shapes how movements organise, how organisations survive, and how futures are imagined.

Treating money as the primary lever for change narrows possibilities and reinforces existing power structures. Understanding money as energy—and not as a resource—creates space for different questions: What capacities already exist? What relationships are underutilised? What systems need redesigning?

Social change has never been driven by money alone. It has always been driven by people, ideas, relationships, and collective action. Money can support those forces, but it cannot substitute for them.

Reframing money is not about rejecting it. It is about putting it back in its proper place—useful, influential, but never the source of transformation itself.