Wildfires in California and Los Angeles have dominated headlines in recent weeks, capturing global attention with scenes of devastation, displacement, and resilience. While most coverage focuses on the visible flames, smoke, and human toll, today’s episode of Changemaker Q&A—hosted by humanitarian educator and founder of the Humanitarian Changemakers Network, Tiyana J—invites listeners to look beneath the surface.

The discussion introduces three powerful systems thinking tools that changemakers can use to make sense of complex challenges: systems mapping, the iceberg model, and the problem tree. Together, these frameworks offer more than a way to analyze crises like wildfires—they equip social change leaders to navigate the interconnected issues behind any social or environmental challenge.

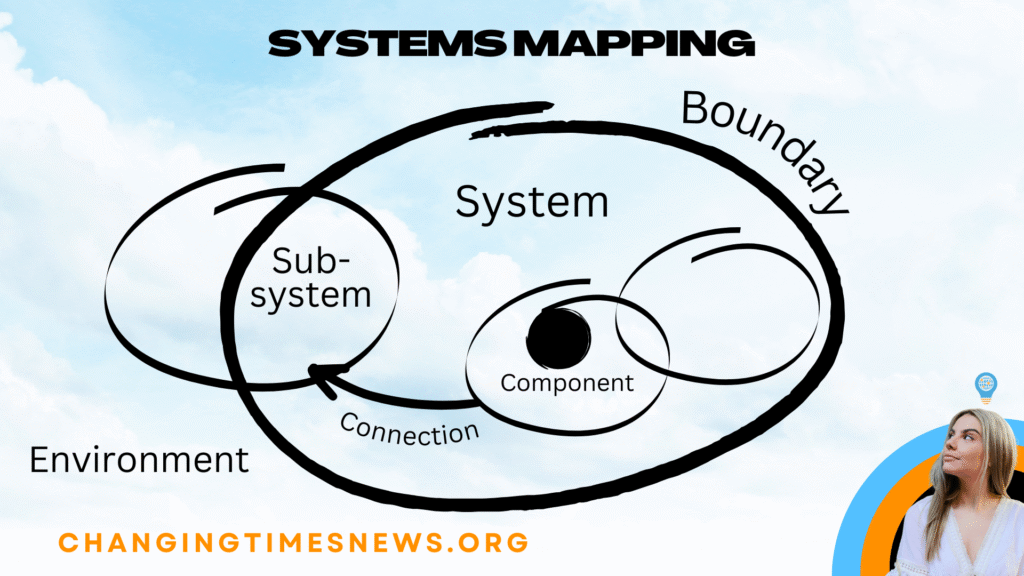

Systems Mapping: Drawing Boundaries in a Complex World

Systems mapping is often the starting point for applying systems thinking. It involves identifying the components of a system, the relationships between them, and the boundaries that distinguish the system from its wider environment.

In the case of the LA fires, mapping reveals a web of natural, social, and economic actors: eucalyptus trees that fuel the blazes, housing developments that push deeper into fire-prone areas, and policies that prioritize privatized firefighting resources. Beyond the local boundary, external drivers such as climate change and global commodity markets shape the risks on the ground.

The approach reflects what experts describe as “soft systems thinking,” which acknowledges that social systems require flexible boundaries and context-specific analysis (see Open University’s Systems Thinking in Practice).

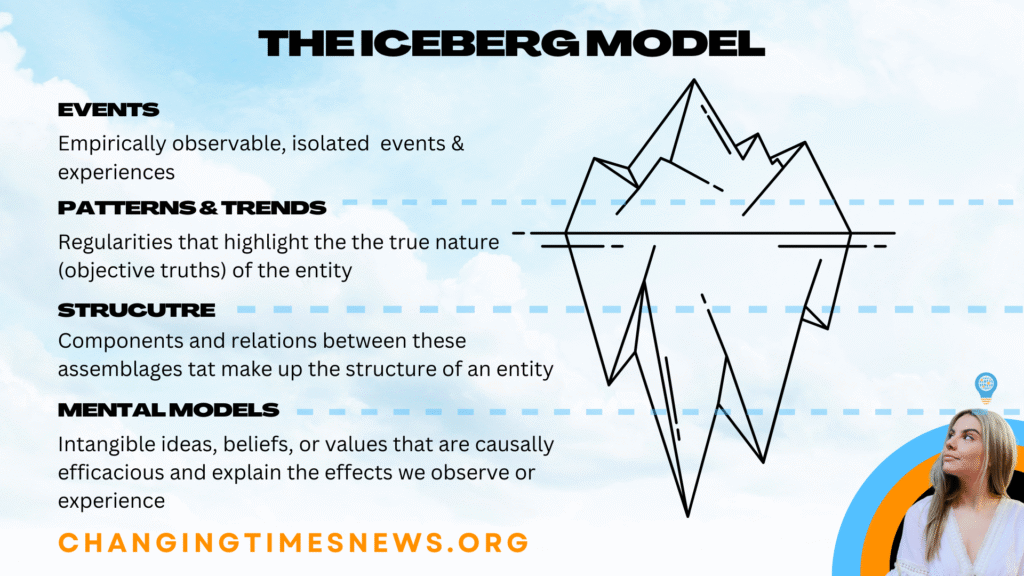

The Iceberg Model: Seeing Beyond the Flames

Borrowing from the metaphor of an iceberg, this tool helps practitioners distinguish between visible events and the deeper patterns, structures, and mental models that sustain them.

For the LA fires, the “tip of the iceberg” includes visible events: evacuations, destruction of homes, and rising insurance costs. Below the surface, patterns reveal the growing intensity of fires and inequitable impacts on low-income communities. Deeper still lie systemic structures, such as inadequate forest management and urban sprawl, and underlying cultural assumptions—like prioritizing economic growth over ecological sustainability.

As Tiyana J notes, the iceberg model allows changemakers to differentiate between symptoms and root causes. This echoes insights from sustainability scholars who argue that transformative change requires addressing underlying cultural and systemic drivers, not just surface-level problems (see Meadows, 2008, Thinking in Systems).

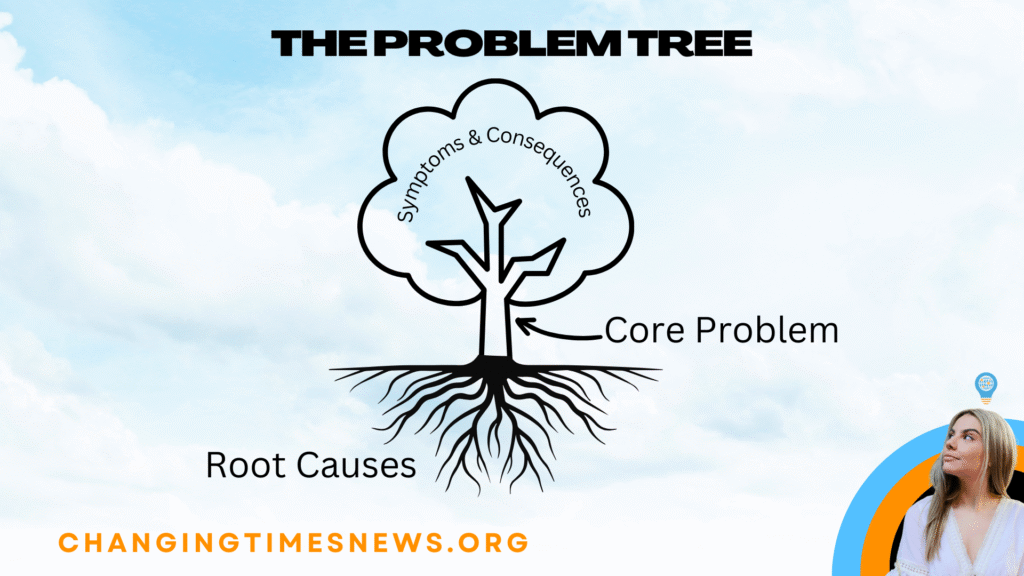

The Problem Tree: Tracing Roots and Consequences

The final tool discussed, the problem tree, visualizes the relationship between symptoms, core issues, and root causes. The “branches” represent consequences such as displacement, biodiversity loss, and health impacts, while the “roots” expose underlying causes like climate change, invasive species, and policy failures.

By connecting these layers, the problem tree highlights the importance of addressing both immediate needs and structural drivers. As Tiyana J explains through a thought experiment: just as firefighters must rescue people while also preventing flames from spreading, changemakers must balance responding to urgent symptoms with tackling systemic causes.

Why It Matters Now

With global warming intensifying wildfire seasons (NASA Earth Observatory), the urgency of systems thinking has never been clearer. Beyond California, communities worldwide are grappling with interconnected crises—climate shocks, economic inequality, and fragile infrastructures. Tools like those explored in this episode help practitioners, activists, and policymakers see the bigger picture and design interventions that respond to complexity rather than oversimplifying it.

For changemakers following the Humanitarian Changemakers Network’s 30-day challenge, these tools also provide practical frameworks for bridging personal reflection with systemic action. Whether applied in exploratory, academic, or collaborative contexts, systems thinking encourages more holistic, equitable approaches to social change.

As Tiyana J emphasizes, the power of these models lies not in abstract theory, but in helping changemakers connect the dots in a fragmented world—transforming the way we understand, and respond to, crises like the LA fires.