It is tempting to treat conservation as a technical problem. A matter for ecologists, protected areas, threatened species lists, and the right mix of interventions. Those elements matter. Deeply. Yet, again and again, the evidence and lived experience converge on a more confronting truth: the hardest part of conservation is not biological complexity. It is social complexity.

In a recent conversation with Tommy—an Irish-based podcaster and outdoorsman who has watched his work evolve from fishing stories to science-and-policy analysis—this reality surfaced with unusual clarity. His journey offers more than an origin story. It offers a lens: the environmental crisis is inseparable from how human societies organise power, set incentives, create narratives, and define “resources”.

From “outdoors” to conservation: when lived experience meets systems

Tommy’s entry point into conservation was not a university pathway or a formal role in the sector. It began with a practical observation that many people who spend time in rivers, forests, and coasts eventually face:

If many people are using the same ecosystem—fishing, hunting, walking, extracting, building—why does it sometimes endure, and why does it sometimes collapse?

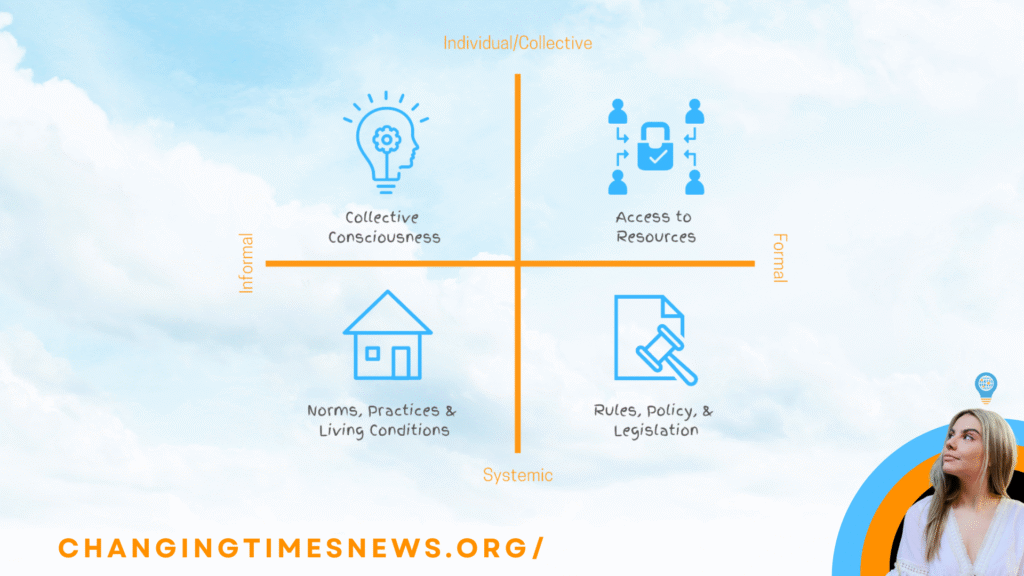

This is a deceptively simple question. It immediately pushes us into the terrain of governance: rules, enforcement, norms, and the social agreements that shape who can take what, when, and with what consequences. In other words, it pushes us into policy.

Over time, Tommy’s podcast shifted accordingly. What began as “outdoors” content expanded into “Conservation and Science” because the content itself demanded it: conservation outcomes are shaped by institutions, political incentives, public attitudes, and competing economic goals. Ecological decline, as he noted, is not only a story of species and habitats. It is a story of human priorities.

This is one reason podcasts, community media, and informal learning platforms have become so influential in the environmental space. They allow people to track the live interface between science and society, without waiting for a decade-long lag between research and public understanding.

The core misconception: not hatred of nature, but disconnection from it

When asked about misconceptions in how humans relate to nature, Tommy did not focus on a single myth about conservation practice. He pointed to something more foundational: widespread disconnection.

Not simply a lack of time outdoors, but a deeper detachment—social, psychological, and cultural. Many people now encounter nature primarily through headlines, documentaries, or social media fragments, rather than through direct relationship and responsibility. Even mild inconvenience is increasingly treated as unacceptable: pests are poisoned, nuisances removed, risk engineered out of life.

That disconnection matters because it shapes what people will tolerate, support, and fund. It also shapes what people can imagine. Societies that experience nature as distant scenery struggle to build political coalitions for ecological repair—particularly when repair involves trade-offs, constraints, or long time horizons.

Tommy offered a striking illustration. He described a pattern where people speak confidently about how communities elsewhere should “live with wildlife,” while they themselves cannot tolerate small, local inconveniences such as ticks in the backyard. The point is not to mock discomfort. It is to expose a mismatch between moral posturing and embodied reality.

Conservation, in this view, is not only about saving wildlife. It is also about restoring humility: recognising that humans are not outside ecosystems, but within them.

Reconnection begins with attention

One of Tommy’s simplest recommendations was also one of the most structurally relevant: put down the phone.

At first glance, it can sound like a personal wellbeing tip. In practice, it is a political statement about attention. The contemporary attention economy does not merely distract; it shapes what people perceive as real. It compresses time horizons. It incentivises outrage over sustained care. It makes slow ecological processes—soil regeneration, species recovery, hydrological cycles—hard to notice and therefore hard to value.

Reconnection, then, begins with attention in the literal sense. Not “caring” in the abstract, but noticing. Observing seasonal shifts. Learning local species. Tracking changes in waterways and tree cover. Paying attention long enough to develop relationship.

This is not nostalgia. It is capacity-building. A society that cannot pay attention cannot govern itself through complex ecological transitions.

Why policy matters, and why politicians follow incentives

Tommy’s second emphasis was structural: conservation outcomes are downstream of policy, and policy is downstream of political incentive. Politicians tend to prioritise what sustains their legitimacy and re-election prospects. This is not cynicism; it is a feature of electoral systems and institutional design.

The implication is straightforward: if enough people care about clean rivers, habitat protection, air quality, ecological restoration, and biodiversity decline—and if they make that care visible through organised civic pressure—policy shifts become more likely.

This is why “small” actions such as writing to local representatives can matter. Not because one letter “changes everything,” but because democracy often responds to patterns rather than single events. Organised, repeated signals change what politicians perceive as safe, popular, and urgent.

A key insight here is that conservation is not only an environmental project. It is a public institutions project.

The danger of moral division: conservation coalitions are made, not found

One of the most significant arguments Tommy made was about strategy: do not build environmental progress by manufacturing enemies.

There is a strong temptation in public debate to simplify blame. Farmers. Fishers. Hunters. Corporations. “Consumers.” “City people.” “Greenies.” These labels can feel satisfying, but they often harden identities and reduce the space for negotiated change.

Tommy offered an alternative: start with what people agree on, then build relationship, then approach the difficult disagreements from a position of trust and shared purpose.

This is not naïve. It is consistent with decades of scholarship on conflict transformation, stakeholder engagement, and deliberative governance. Complex environmental problems routinely involve trade-offs between livelihood security, cultural identity, and ecological protection. Durable solutions require coalitions. Coalitions rarely emerge from moral contempt.

A practical example he gave was simple but instructive: if a farmer wants to build a pond, start there. Help. Co-create. Strengthen the shared value of habitat. Then, once relationship exists, the harder discussions—nutrient runoff, stocking rates, chemical inputs, land management incentives—become more possible.

In this approach, conservation becomes a relational practice. Not only a scientific practice.

Hunting, ethics, and the uncomfortable honesty of death

The conversation also entered ethically charged territory: hunting, fishing, and the status of animals as “resources.”

Tommy acknowledged the discomfort some people feel with that language while also noting its historical and managerial roots. Conservation itself is often framed as conserving “resources”—a framing that can obscure the intrinsic value of non-human life, yet also shapes how institutions govern ecosystems.

On hunting specifically, he rejected both caricatures: the “mindless killer” stereotype and the uncritical romanticisation sometimes found within hunting cultures. He argued that many hunting traditions function as rituals of reflection, creating a moment between death and consumption in which hunters confront what has occurred. This is important because it recognises a psychological and moral reality: killing is not neutral, even when culturally sanctioned or ecologically managed.

This is where the discussion intersected with a broader cultural critique: modern societies often struggle to hold death as part of life. Avoidance of death can be expressed as denial, sanitisation, and distance. The industrial food system intensifies this by separating consumers from slaughter and land-use impacts. Hunting, for all its controversies, can reduce that distance—though only when practised with competence, respect, and a serious ethic of welfare.

For Changing Times readers, the broader point is this: environmental ethics cannot be reduced to simple identity labels (“vegan,” “hunter,” “farmer,” “activist”). The question is not who you are. The question is what relationships your choices create—between humans, animals, ecosystems, and institutions.

Rewilding: a hopeful idea, and a contested term

Rewilding is rising rapidly in popular discourse. Tommy observed something that conservation researchers and practitioners increasingly recognise: the term carries multiple meanings and is therefore vulnerable to politicisation.

For some, rewilding signals ecological restoration and the return of natural processes. For others, it is heard as a threat—an anti-rural agenda, a land-use shift that undermines community livelihoods, or a project imposed by urban elites.

In such contexts, language matters. Tommy’s argument was pragmatic: where the term triggers immediate shutdown, use other terms that may be more precise and less inflammatory, such as ecological restoration or habitat recovery.

He also highlighted an essential principle: meaningful rewilding requires time and space. It is not a short project cycle. It is a commitment to letting ecological processes re-establish themselves, ideally at sufficient scale to reduce “conservation dependence” (where ecosystems survive only as long as funding and political will endure).

This is a useful caution in an era of branding-heavy sustainability discourse. When environmental language becomes a slogan, it can be used to sell narratives rather than build ecosystems.

Where hope sits: youth, politics, and the inevitability of adaptation

Tommy located hope in young people—those who are increasingly aware of ecological decline and increasingly unwilling to accept “business as usual.” He also offered a sobering framing: in many respects, younger generations have less choice. Climate disruption and biodiversity loss are not abstract futures; they are emerging conditions that will shape livelihoods, health systems, and social stability.

Hope, then, is not passive optimism. It is the possibility of organised adaptation and transformative change. And, as he emphasised, that change flows through politics. Not only electoral politics, but local governance, policy advocacy, and community organising.

In other words, hope is not a feeling. It is a strategy.

What this episode leaves us with

If there is a single through-line in this conversation, it is this: conservation is not only about what we protect. It is about how we live.

It is about attention, relationship, and governance. It is about resisting the urge to moralise our way into division, and instead building coalitions capable of holding complexity. It is about recognising that ecological “solutions” cannot succeed without social legitimacy and institutional change.

Most of all, it is about reconnection—not as a lifestyle aesthetic, but as a collective practice of remembering that humans are participants in ecosystems, not managers standing outside them.

That shift, once taken seriously, changes everything.