Few ideas provoke as much immediate discomfort as the suggestion that people in wealthy societies should become poorer. The discomfort is revealing. It exposes how deeply prosperity has been tied, culturally and politically, to paid work, consumption, and economic growth. In his conversation on Voices of the New Economy, Robert McLean challenges this assumption directly, proposing a four-hour work day as a pathway towards reduced energy use, stronger communities, and a more liveable future in the context of climate breakdown.

Robert’s proposal is not framed as a lifestyle preference or a productivity hack. It is presented as a systemic intervention, grounded in the recognition that climate change is not a peripheral problem, but the defining challenge facing human societies. From this starting point, the logic is stark. If climate change is driven by energy use and material throughput, then meaningful responses require structural reductions in both. Efficiency gains alone are insufficient. What is required is a deliberate slowing down of economic activity in wealthy nations.

Climate Change as a Structural Problem

At the heart of Robert’s argument lies a simple observation: energy not used is energy saved. Working fewer hours would reduce commuting, particularly long-distance travel that locks people into car dependence. It would encourage people to live closer to where they work, making walking, cycling, and public transport more viable. Reduced income would also constrain consumption, limiting the constant replacement of goods that characterises growth-oriented economies.

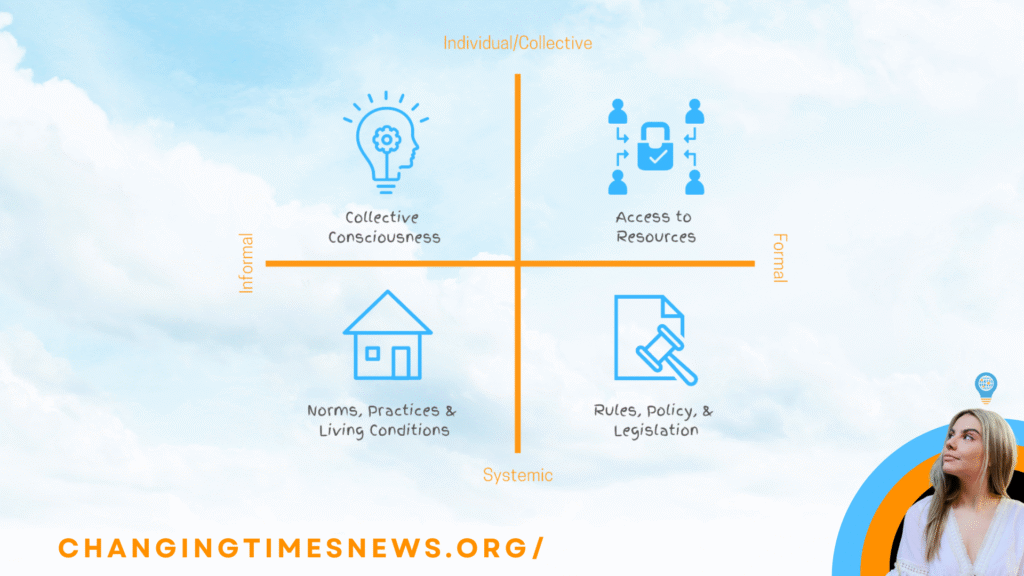

These changes are not framed as individual lifestyle adjustments, but as collective outcomes of structural redesign. The four-hour work day functions as a lever that simultaneously reshapes labour, transport, and consumption patterns. In doing so, it shifts responsibility for climate action away from personal virtue and towards systemic change.

Financial Poverty and Social Wealth

A central and confronting claim in Robert’s proposal is that people in wealthy countries would need to become financially poorer. This is often interpreted as a threat to wellbeing. However, Robert reframes financial poverty as distinct from social and emotional deprivation. Rather than diminishing quality of life, he argues that working less could expand forms of wealth that are currently crowded out.

Time freed from paid employment could be redirected towards community life, care, creativity, and mutual support. Activities such as growing food, repairing homes, sharing skills, and simply knowing one’s neighbours would become more feasible. In this framing, work becomes a secondary activity, while the primary work of sustaining community and place moves to the centre.

Redefining Work and Value

The four-hour work day also challenges narrow definitions of work that dominate contemporary economic thinking. Much of the labour that sustains societies — caregiving, volunteering, ecological stewardship — is unpaid or undervalued. By redistributing time rather than income alone, the proposal implicitly questions why certain forms of work are recognised and rewarded, while others remain invisible.

This reframing aligns with broader critiques of growth-oriented economies that prioritise productivity over wellbeing. It suggests that the purpose of economic activity should be to support life, rather than to maximise output.

Why the Idea Feels Impossible

Resistance to the four-hour work day is not simply practical. It is cultural and historical. Robert traces this resistance to the consolidation of neoliberal economic thought in the mid-twentieth century, often associated with institutions such as the Mont Pelerin Society. Since that period, growth, competition, and market expansion have been normalised as common sense, shaping both policy and everyday expectations.

Within this paradigm, working less appears irresponsible or unrealistic. The proposal disrupts deeply held beliefs about success, morality, and contribution. It also exposes the extent to which identities and security are bound to employment, making alternative arrangements difficult to imagine.

Big Ideas Before Policy Detail

Importantly, Robert does not present the four-hour work day as a fully specified policy program. Instead, he emphasises the need to start with a clear direction. Societies, he argues, often decide on ambitious goals first and work out the technical details later. In this sense, the proposal functions as a provocation, creating space to think beyond incremental reform.

This approach challenges a political culture that demands immediate feasibility while continuing with arrangements that are demonstrably unsustainable. It also shifts responsibility back to institutions and governments, rather than individuals, to design pathways for transition.

Media, Imagination, and the Limits of Debate

Drawing on his background in journalism, Robert reflects on the role of media in shaping public understanding of what is possible. Media organisations embedded in growth-dependent business models have limited capacity to promote ideas that challenge consumption and economic expansion. As a result, radical alternatives are often dismissed as utopian or unrealistic.

Yet Robert insists that utopian thinking is essential. Without the ability to imagine fundamentally different arrangements, societies remain trapped within trajectories that are increasingly incompatible with ecological reality. One phrase he returns to captures this tension: revolution sometimes means remaining loyal to the impossible.

Choosing a Different Way

Ultimately, the four-hour work day is less a fixed solution than an invitation to rethink priorities. It asks what people in wealthy societies are willing to relinquish in order to protect future generations. It reframes climate action as a collective choice about how to live, rather than a series of individual sacrifices.

As Robert emphasises throughout the conversation, the crises facing humanity are not accidental. They are the result of choices. Different choices remain possible. Whether societies are prepared to make them is the question that lingers.