Across the social change sector, people are often motivated by strong values, moral clarity, and a deep commitment to justice. These commitments are not incidental. They are foundational to why people enter activism, development, policy, humanitarian work, or systems change in the first place. Yet one of the most confronting realities of this work is that change rarely unfolds under ideal conditions. Social change is shaped by power, resources, institutions, and historical constraints. As a result, trade-offs are unavoidable.

Trade-offs are frequently experienced as frustration, disappointment, or even ethical compromise. However, they are not evidence that something has gone wrong. Rather, they are a structural feature of working within complex systems that are already in motion. Understanding trade-offs as inherent to social change—rather than as moral failure—can help practitioners navigate complexity without losing their sense of purpose.

Why Trade-Offs Exist in the First Place

Social change never begins on a blank canvas. Interventions, campaigns, and reforms are always introduced into existing political, economic, cultural, and institutional systems. These systems already have embedded norms, incentives, power relations, and path dependencies that shape what is possible at any given moment.

Several conditions make trade-offs inevitable:

- Limited resources, including time, funding, political capital, and human capacity

- Uneven power, where some actors have far greater influence than others

- Competing priorities, often between short-term urgency and long-term transformation

- Institutional constraints, such as policy cycles, donor requirements, or legal frameworks

Prioritising one outcome necessarily means deprioritising another. This is not a reflection of weak values; it is a consequence of finite capacity within complex systems.

A useful reframe is that limitations do not merely constrain action—they shape it. Constraints can generate creativity, strategy, and distinct approaches to change. In this sense, trade-offs are not obstacles to overcome but conditions to work with.

Trade-Offs in Activism and Campaigning

Activism often operates under conditions of urgency, responding to immediate harm or injustice. This urgency can intensify trade-offs, particularly between clarity of values and breadth of engagement.

One of the most common tensions is between purity and reach.

- Maintaining a clear, uncompromising position can strengthen internal coherence and moral clarity.

- Broadening a message can expand participation and coalition-building but may require simplification or compromise in language and framing.

Neither approach is inherently correct. Each reflects a strategic choice about how change is expected to occur. Movements that prioritise purity may deepen commitment among a smaller group, while those that prioritise reach may achieve wider influence at the cost of internal discomfort.

These tensions are not unique to activism. They reflect a broader challenge of balancing ethical consistency with practical influence.

Trade-Offs in Politics and Policy

Politics makes trade-offs highly visible. Governing almost always involves choosing between imperfect options under institutional constraints.

Common political trade-offs include:

- Ideal policy versus politically feasible policy

- Short-term wins versus long-term structural reform

Policies that align strongly with evidence and values may lack sufficient political support to pass. Incremental reforms may deliver partial improvements while leaving deeper systemic drivers untouched. Conversely, transformative reforms often face resistance and delayed outcomes.

These decisions can feel deeply uncomfortable, particularly for those committed to justice and fairness. Yet they reflect the reality of working within political systems shaped by electoral cycles, competing interests, and institutional inertia.

Trade-Offs in Development and Humanitarian Work

Development and humanitarian interventions are especially constrained by funding timelines, donor priorities, and measurement frameworks. These constraints frequently produce tensions between how change is understood and how it must be reported.

Two recurring trade-offs are particularly prominent:

Participation versus Speed

Genuine community-led processes require time, trust-building, and iterative learning. In emergency or tightly funded contexts, pressure to act quickly can limit participation and local ownership.

Scale versus Depth

Programs designed to reach large populations often rely on standardisation, which can overlook local context and nuance. Smaller, context-specific initiatives may support deeper change but struggle to attract funding or demonstrate scale.

These trade-offs do not indicate poor design. They reflect structural features of the development system itself.

Trade-Offs as a Feature of Complex Systems

From a theoretical perspective, trade-offs are central to systems thinking, policy analysis, and environmental governance. In economics, this is captured by the concept of opportunity cost: choosing one option necessarily means forgoing another.

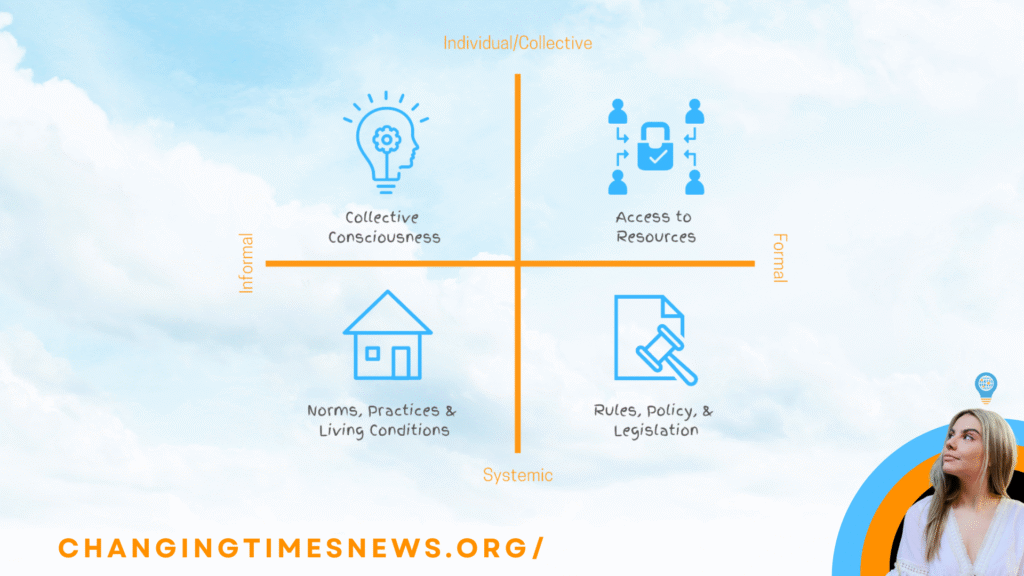

In social and ecological systems, trade-offs are often categorised as:

- Spatial trade-offs, where benefits and costs are distributed across different locations

- Temporal trade-offs, where short-term gains undermine long-term sustainability

- Distributional trade-offs, where some groups benefit while others bear the costs

Challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion are shaped by these overlapping trade-offs. No intervention can maximise all outcomes simultaneously.

Frameworks for Navigating Trade-Offs More Deliberately

Rather than eliminating trade-offs—which is impossible—social change work benefits from making them explicit and intentional.

Several approaches can assist:

- Systems frameworks that distinguish between simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic contexts, helping tailor decision-making approaches

- Multi-criteria decision analysis, which evaluates competing priorities such as equity, feasibility, cost, and impact

- Theory of change and outcome-focused tools, which map likely consequences across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons

- Adaptive management, which treats decisions as provisional and responsive to feedback rather than fixed commitments

These approaches shift decision-making away from false certainty and toward learning, reflection, and adjustment.

Why Acknowledging Trade-Offs Builds Stronger Movements

Trade-offs become most damaging when they are hidden, denied, or framed as personal failure. When acknowledged openly, they can strengthen trust, accountability, and resilience.

What matters is not whether trade-offs exist, but:

- Who is involved in making them

- Whether they are guided by values or convenience

- Who bears the costs and who benefits

- Whether they can be revisited as conditions change

Movements and organisations that can speak honestly about trade-offs are often better positioned to adapt, learn, and sustain legitimacy over time.

Living With Imperfection Without Losing Purpose

Social change is not the pursuit of perfect solutions. It is the ongoing work of navigating complexity with integrity. Trade-offs are not a sign that values have failed; they are evidence that values are being tested in the real world.

Rather than asking how to avoid trade-offs, a more productive question is how to make them consciously, ethically, and transparently. In doing so, changemakers can remain grounded in their purpose while engaging realistically with the systems they seek to transform.

Trade-offs, when approached with clarity and care, are not the enemy of social change. They are part of its terrain.