For many in the social change space, the idea of pursuing a PhD comes wrapped in both excitement and uncertainty. On one hand, it promises years of deep focus on a topic that matters to you, access to institutional resources, and a globally recognized qualification. On the other, it demands years of intense work, a stipend that often sits below minimum wage, and no guarantee of a clear career path afterward.

In a recent episode of Changemaker Q&A, Humanitarian Changemakers Network founder and PhD candidate Tiyana J explored these tensions, offering candid insights into what it means to take on a higher research degree as someone committed to creating impact.

Beyond Career Moves: Potential and Purpose

For most people, the question of whether to do a PhD is framed as a career decision: Will this degree help me get a job, earn more money, or progress in my field? But for changemakers, Tiyana suggests, the calculation is more layered.

“It’s not simply a question of whether this decision is right for your career,” she explains. “It’s also a question of whether it’s the best use of your potential for impact.”

That means considering not only what a PhD might do for your CV, but whether the research itself — or the skills you’ll gain through it — is the most effective way for you to contribute to the change you want to see.

A Framework for Thinking About Work

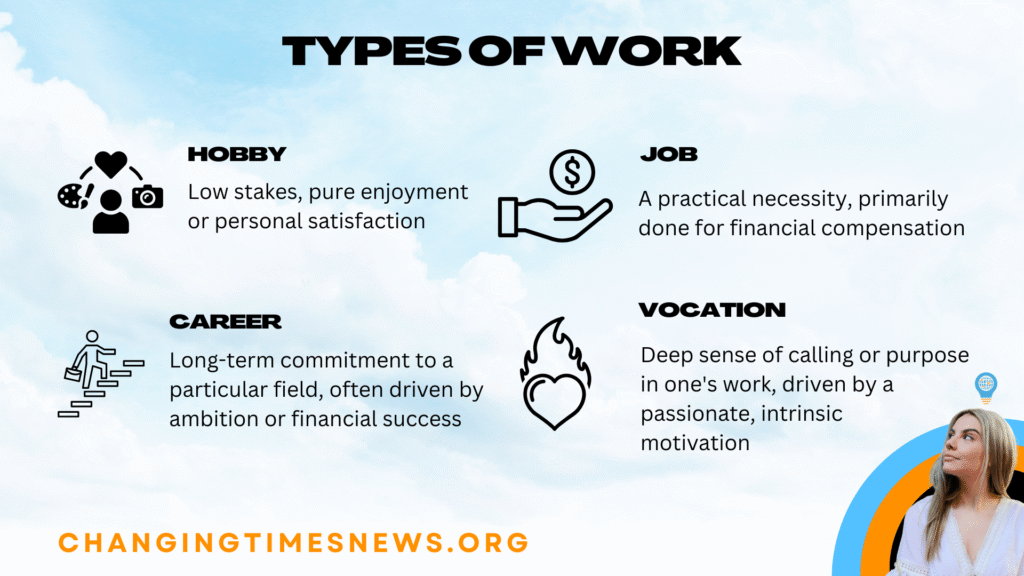

To unpack this, Tiyana turns to a framework borrowed from Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear. Gilbert distinguishes four types of work: hobbies, jobs, careers, and vocations.

- Hobbies are pursued for joy and creativity, without expectation of pay.

- Jobs are about financial stability, not necessarily passion or meaning.

- Careers involve long-term commitment to a field, driven by ambition or recognition.

- Vocations are callings — intrinsically motivated pursuits tied to purpose and meaning.

Tiyana applies this to social change work. For some, activism or advocacy might be a hobby. For others, it becomes a career. For many, it is a vocation — work pursued less for financial return than for its alignment with a deeper sense of purpose.

Want to learn more about living a life of impact?

Access free resources and training as part of our Empowered Agents of Change toolkit via the FREE Social Impact Foundations course on the School of Social Impact.

A PhD, she argues, is rarely a hobby or a job. Instead, it usually sits at the intersection of career and vocation: a stepping stone that opens professional opportunities, or a deeply personal pursuit of knowledge and impact.

The Realities of PhD Life

That dual nature brings both benefits and challenges. On the one hand, PhD students gain research skills, project management experience, and access to networks and resources unavailable elsewhere.

“You’re essentially given three to four years to choose your own project, plan and manage it, and be supported to carry it out,” Tiyana reflects. “That’s an opportunity you don’t really get in most careers.”

But the financial side is sobering. In Australia, the standard PhD stipend sits around AUD $35,000 per year — tax free, but below the minimum wage. A 2022 survey of Australian postgraduates found that more than 40% experienced financial hardship during their studies (CAPA, 2022). For those with families or existing financial commitments, the pay cut can be a significant barrier.

“The stipend is really just enough to cover basic living expenses,” Tiyana notes. “If you have a partner or children, it’s something you need to think through carefully.”

Timing and Motivation Matter

So when is the right time to start? For Tiyana, the decision came during the upheaval of 2020. With travel plans halted by the pandemic, she saw an opportunity in a dual PhD program between the University of Queensland and a leading Indian university. The project aligned perfectly with her passion for communication and social change — a field outside her formal academic background but deeply connected to her purpose.

“If I was ever going to do a PhD, this was the project I wanted to do,” she says.

Her advice to others: be intentional. Ask whether you’re pursuing a PhD primarily as a career step — to build skills, credibility, and opportunities — or as a vocation, to pursue a project that aligns deeply with your passions. Both are valid, but the expectations and sacrifices differ.

Aligning with Your “Why”

Ultimately, Tiyana encourages changemakers to ground the decision in their sense of purpose. Drawing on Simon Sinek’s Start With Why, she suggests mapping out three layers:

- Why: your purpose as a changemaker — the impact you want to make.

- How: the different avenues you could pursue to achieve that impact.

- What: the concrete actions, such as enrolling in a PhD.

If research emerges as one of your “hows,” then a PhD might be a powerful tool. But if your purpose aligns more closely with grassroots activism, policy work, or community organizing, there may be other, more effective paths.

No One-Size-Fits-All Answer

As universities increasingly encourage higher research degrees, the decision to enroll can feel like the “expected” next step. Yet the reality is more nuanced. A PhD can be transformative, but it is not the only — or even the best — way to create social impact.

“There’s no right or wrong way,” Tiyana emphasizes. “What matters is being intentional about the relationship you have with your work and your impact.”

For changemakers weighing their next step, the message is clear: a PhD can be a career boost, a vocational calling, or both. But before diving in, it’s worth asking not just “Is this right for my career?” but “Is this the best use of my potential for change?”