Over the past decade, mindfulness has moved from spiritual and philosophical traditions into mainstream culture. It appears in corporate wellbeing programs, productivity apps, and self-care routines, often framed as a tool for stress reduction and individual resilience. While these practices may offer short-term relief, they rarely question the social, political, and economic systems that generate stress in the first place.

For people working in social change—activists, community organisers, policy advocates, and practitioners—this narrow framing is insufficient. When mindfulness is reduced to a personal coping mechanism, it risks becoming a form of quiet adaptation to unjust conditions rather than a force for transformation. What is needed instead is a broader, more systemic understanding of mindfulness—one that recognises how awareness, reflexivity, and intention operate across multiple dimensions of human life.

Mindfulness Beyond the Individual

Conventional approaches to mindfulness tend to focus on the inner world: thoughts, emotions, and personal stress responses. This emphasis has value, but it also reflects a deeper cultural assumption that responsibility for wellbeing lies primarily with individuals. In highly unequal and extractive systems, this can become a subtle form of displacement, shifting attention away from structural harm and onto personal regulation.

A more robust approach recognises that human experience is not confined to the inner psyche. People exist simultaneously as physical bodies, social actors, institutional subjects, and relational beings. Mindfulness, if it is to be genuinely transformative, must engage with all of these dimensions rather than isolating one from the others.

Four Planes of Being

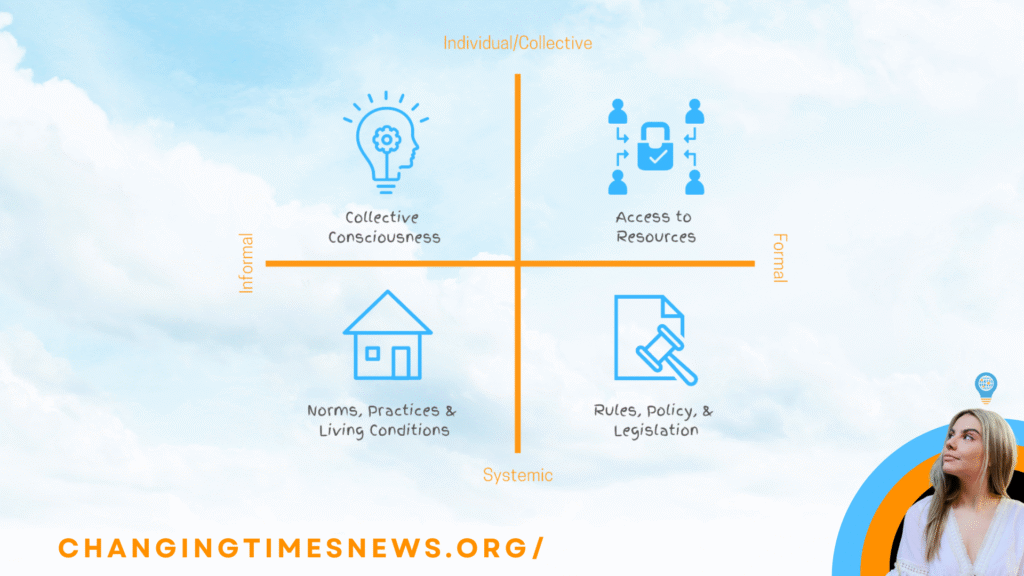

A multidimensional understanding of mindfulness begins with recognising that social beings exist across four interconnected planes of being. Each plane shapes how power is experienced and how awareness can be cultivated.

The material plane refers to physical existence: bodies, environments, and interactions with the natural world. The psychosocial plane encompasses thoughts, emotions, identity, and inner narratives. The structural plane involves institutions, systems, and formal roles within society. The relational plane concerns interactions, relationships, and collective life.

Mindfulness operates differently across each of these planes, yet remains deeply interconnected. Awareness cultivated in one domain inevitably shapes experience in the others.

Mindfulness on the Material Plane

On the material plane, mindfulness is grounded in bodily awareness and environmental attunement. For those engaged in social change, this includes recognising how stress, burnout, and urgency manifest physically. Activism often places sustained demands on the body, yet physical wellbeing is frequently deprioritised in cultures of constant mobilisation.

Material mindfulness also extends to resource consciousness. This involves reflecting on how movements consume time, energy, materials, and ecological resources, and whether these patterns align with the values they seek to promote. In this sense, mindfulness becomes a practice of sustainability, encouraging more deliberate and regenerative ways of working.

Mindfulness on the Psychosocial Plane

The psychosocial plane is where most conventional mindfulness practices are situated. Here, mindfulness supports self-awareness, emotional regulation, and reflection on identity and motivation. For changemakers, this work is essential. Social change efforts are shaped by beliefs, assumptions, and emotional responses that often go unexamined.

Mindfulness at this level helps individuals recognise bias, manage reactivity, and respond with greater intentionality in high-pressure situations. It also enables deeper reflection on how personal identity intersects with power, privilege, and positionality within movements.

Mindfulness and Social Structures

The structural plane introduces a dimension of mindfulness that is largely absent from mainstream discourse. This involves awareness of institutions, systems, and roles that shape social life. Mindfulness here is not about acceptance, but about critical engagement.

Practised at this level, mindfulness supports systems thinking: the ability to see patterns, feedback loops, and unintended consequences. It encourages reflection on how roles—such as leader, professional, citizen, or consumer—shape behaviour and influence outcomes. Rather than reinforcing institutional norms unconsciously, mindful engagement creates space for critique, resistance, and redesign.

This approach reframes mindfulness as a political capacity. Awareness becomes a prerequisite for strategic action, enabling movements to address root causes rather than symptoms.

Mindfulness in Relationships and Movements

The relational plane highlights mindfulness as a collective practice. Social change is inherently relational, yet conflict, fragmentation, and burnout are common within movements. Mindfulness in this domain focuses on listening, empathy, and collaboration.

Relational mindfulness supports deeper understanding across difference, including ideological disagreement. It encourages humility and openness, recognising that knowledge is distributed and that collective intelligence emerges through interaction. When practised intentionally, it strengthens trust and resilience within movements, making long-term collaboration possible.

From Coping to Transformation

Taken together, these four dimensions reveal mindfulness not as a retreat from the world, but as a way of engaging with it more fully. Rather than serving solely as a coping strategy, mindfulness becomes a reflexive capacity that informs ethical decision-making, strategic action, and systemic transformation.

This reframing challenges the commodification of mindfulness and its separation from questions of power and justice. It positions mindfulness as something that belongs not only to individuals, but to communities and movements seeking to reshape the conditions of collective life.

Towards a Transformative Practice

A multidimensional approach to mindfulness does not reject personal wellbeing. Instead, it situates wellbeing within broader social contexts. It recognises that sustainable social change requires attention to bodies, minds, institutions, and relationships simultaneously.

For changemakers, this perspective offers a way to remain grounded without becoming disengaged, and reflective without becoming passive. Mindfulness, when understood in this fuller sense, becomes less about adapting to the world as it is, and more about cultivating the awareness necessary to change it.