When it comes to creating lasting social change, sometimes the most powerful action is not immediate action at all—but observation. That’s the message at the heart of the latest episode of Changemaker Q&A, where host and Humanitarian Changemakers Network founder, Tiyana J, explores how the permaculture principle of “observe and interact” can inform both design thinking and systems thinking approaches.

Permaculture, first developed in the late 1970s by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, is often described as a sustainable design framework rooted in the idea of “permanent agriculture” and, more broadly, “permanent culture” Holmgren Design. While it began as a model for ecological farming, its principles have since influenced fields as diverse as community development, education, and urban planning.

Observation as Foundation

In permaculture, observation is not a passive activity. It means spending time immersed in an environment—whether that’s a backyard garden or a rural development project—carefully noticing relationships, patterns, and processes before stepping in with interventions. Interaction, meanwhile, emphasizes that humans are not separate from ecosystems or social systems but active participants within them.

This framing echoes Indigenous knowledge systems, where design has long been practiced in harmony with land and community rather than imposed upon them. Scholars such as Tyson Yunkaporta, author of Sand Talk, have argued that Indigenous ways of knowing often embed observation and interaction as continuous, relational processes rather than one-off assessments Text Publishing.

From Soil to Social Systems

While “observe and interact” may sound like advice best suited for gardeners, its relevance extends far beyond agriculture. Tiyana J argues that thorough observation helps changemakers identify root causes of social challenges, rather than treating surface-level symptoms. It also fosters adaptability, builds trust with communities, and ensures interventions are culturally sensitive and effective.

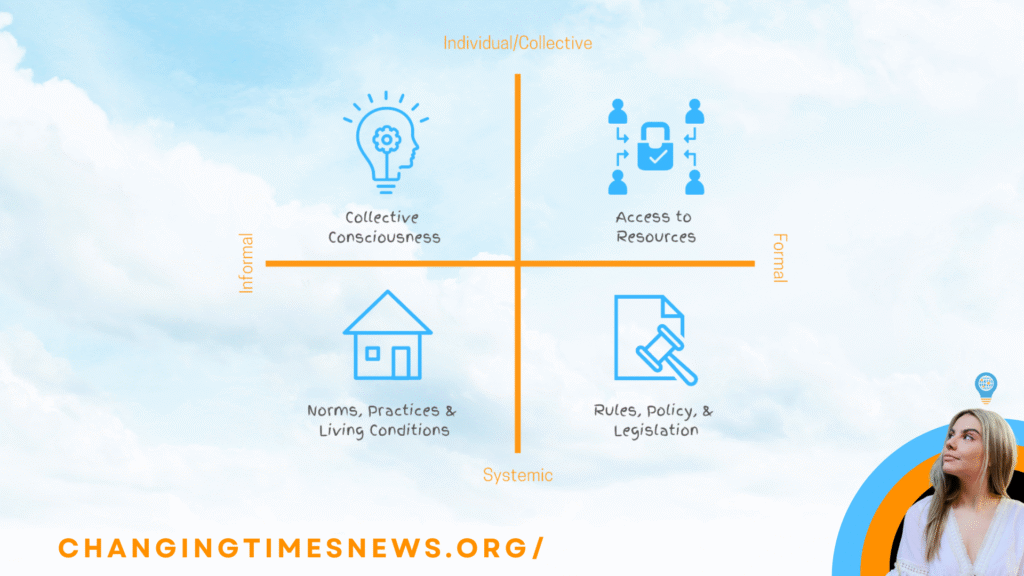

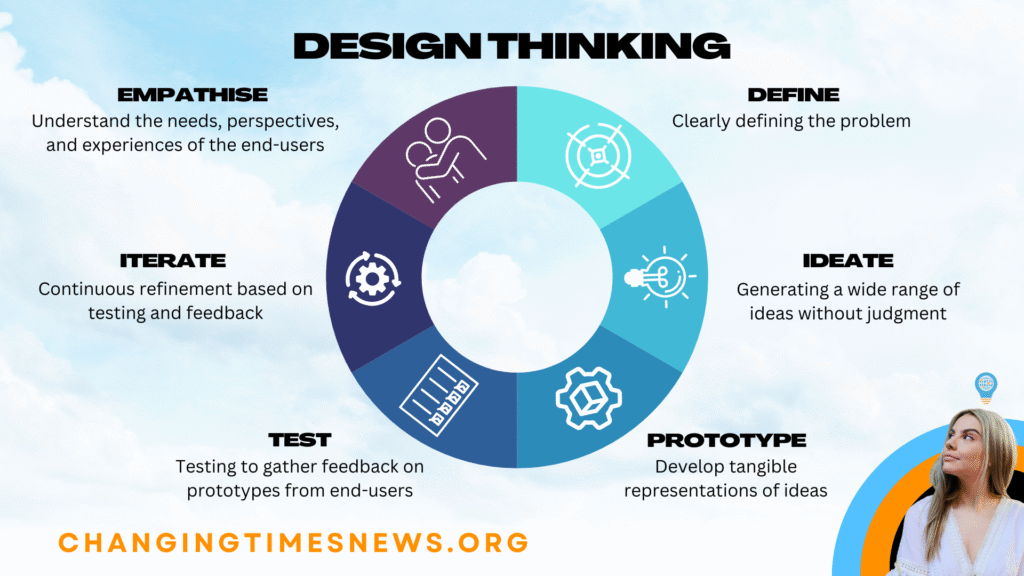

Here, design thinking and systems thinking intersect. Systems thinking emphasizes mapping the interconnections and feedback loops within a system, often starting with simple tools such as causal loop diagrams or SWOT analyses. Design thinking, in contrast, prioritizes empathy and iterative prototyping to solve human-centered problems. Both, however, hinge on careful observation and meaningful interaction.

“Systems thinking helps us to understand the system,” Tiyana notes, “while design thinking helps us to solve problems within that system.”

Why It Matters Now

At a time when social, ecological, and economic systems face mounting pressures, the call to slow down and observe before acting may seem counterintuitive. But research suggests it could be critical. A 2023 report from the Stockholm Resilience Centre emphasized that sustainable transformations depend on “deep listening to ecosystems and communities” before designing interventions Stockholm Resilience Centre.

For changemakers navigating complexity, “observe and interact” offers more than a gardening tip. It is an invitation to reimagine how we learn, design, and act—anchoring social change in patience, humility, and connection.