When it comes to driving social change, it’s tempting to think in straight lines. If you do X, you get Y. Implement a program, measure the outputs, track the outcomes. But what if this tidy, linear model of cause and effect is too simplistic for the messy realities of human societies?

In the latest episode of Changemaker Q&A, I unpack why changemakers need to move beyond traditional cause-and-effect thinking, and instead adopt a more layered view of causality that reflects the complexity of real-world systems.

Why Linear Models Fall Short

For decades, the dominant model of causality in Western thought has been linear. Rooted in the classical scientific method, this model isolates variables, controls conditions, and looks for repeatable results. While useful in laboratories and physical sciences, it quickly breaks down when applied to social systems.

Social life is shaped by feedback loops, interdependent factors, and emergent dynamics. Interventions that succeed in one context often fail in another—not because the work was flawed, but because conditions, histories, and power structures differ. As systems thinker Donella Meadows observed, “We can’t control systems, but we can dance with them” (Meadows Institute).

Introducing Causal Structure

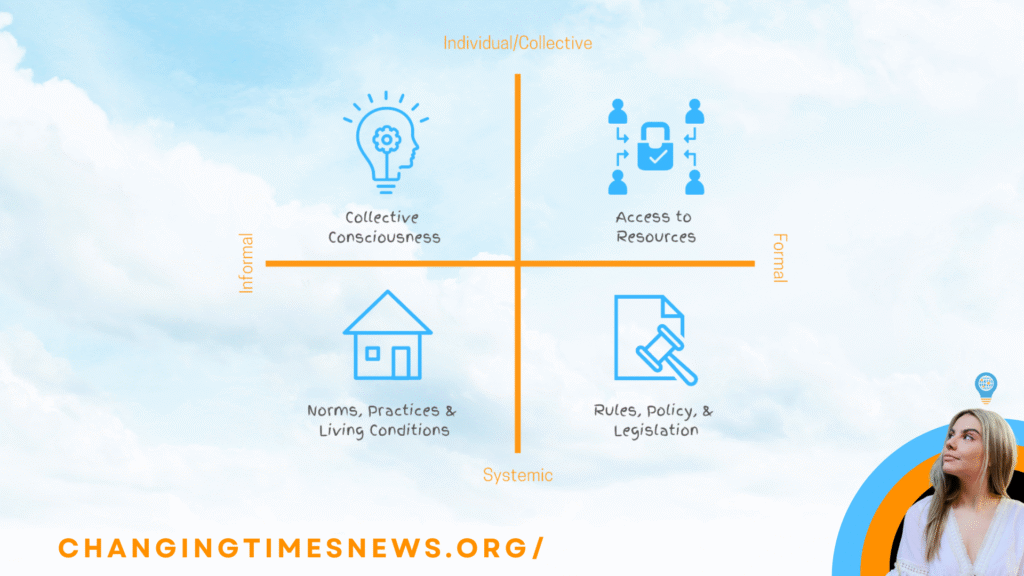

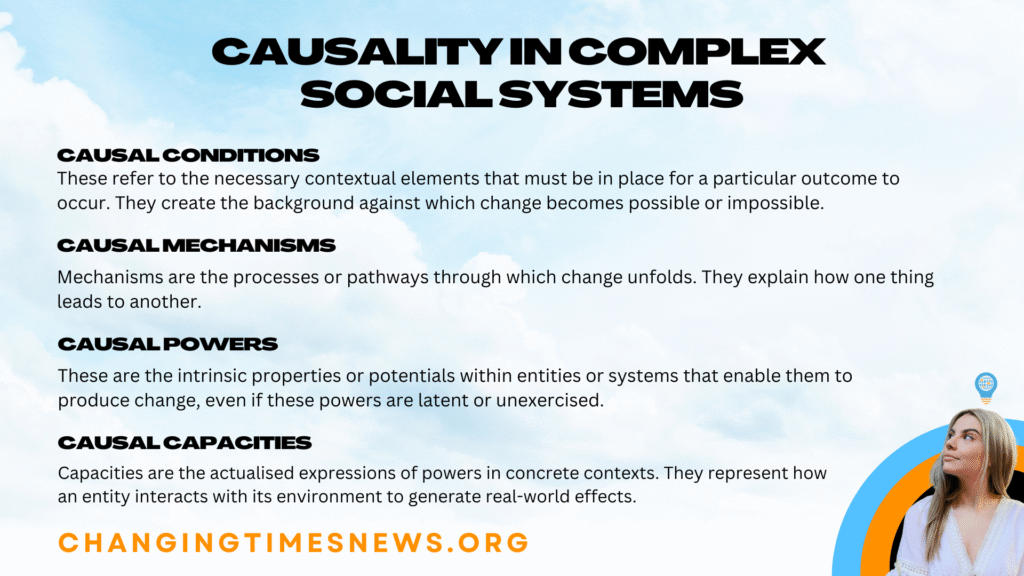

In the episode, I introduce a framework I call causal structure, which moves beyond simplistic inputs and outputs to capture four interconnected dimensions of causality:

- Causal conditions: the backdrop factors (like institutions, norms, or environments) that enable or constrain change.

- Causal mechanisms: the processes that actually drive change forward, such as shifts in beliefs or institutional reforms.

- Causal powers: the latent potential within people, communities, or systems—the possibilities that may or may not be activated.

- Causal capacities: the realized abilities to generate outcomes in specific contexts, shaped by both internal strengths and external constraints.

These distinctions remind us that change is not only about action, but also about timing, context, and possibility.

Lessons for Changemakers

For changemakers—whether in activism, policy, education, or development—embracing causal structure means designing interventions that are:

- Context-sensitive: tailored to the conditions and histories of a community.

- Adaptive: responsive to feedback and unexpected outcomes.

- Rooted in systems thinking: focused on leverage points and ripple effects, not just isolated events.

This echoes insights from the field of complexity science, which stresses that small interventions can have outsized effects when systems are primed, but may yield little when conditions are misaligned (Santa Fe Institute).

Beyond Inputs and Outputs

Linear models persist because they offer simplicity and predictability—qualities valued in strategic plans and funding reports. Yet changemakers working on complex issues such as poverty, gender-based violence, or climate justice know that reality is rarely so straightforward.

By adopting a more nuanced understanding of causality, we can move from rigid logic models to approaches that reflect the emergent, relational, and dynamic nature of change. In doing so, we set ourselves up not just to react to problems, but to cultivate sustainable, systemic transformation.