In a world increasingly fraught with natural disasters, conflict, and emergent crises, the humanitarian and development sectors play pivotal — but often misunderstood — roles in shaping resilience and social change. In the latest Changemaker Q&A, host Tiyana J delves into how disaster preparedness, humanitarian relief, development, and stabilization interconnect within the broader ecosystem of change.

What are the Sectors, and How Do They Differ?

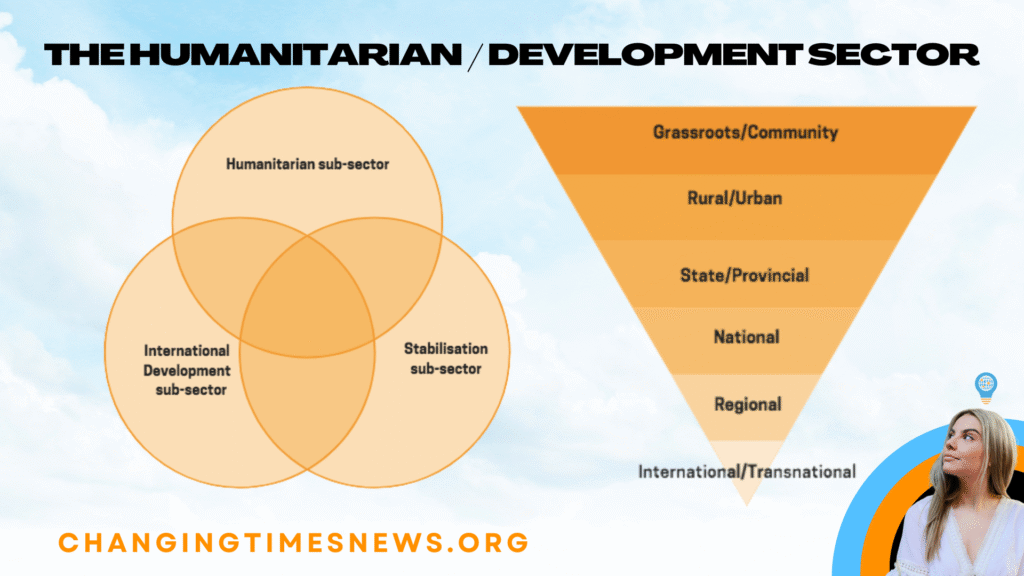

The episode explains that the humanitarian/development sector is not a monolith but rather comprises three overlapping subsectors:

- Humanitarian — Immediate crisis response: life‐saving aid like food, shelter, medical care after disasters or conflict.

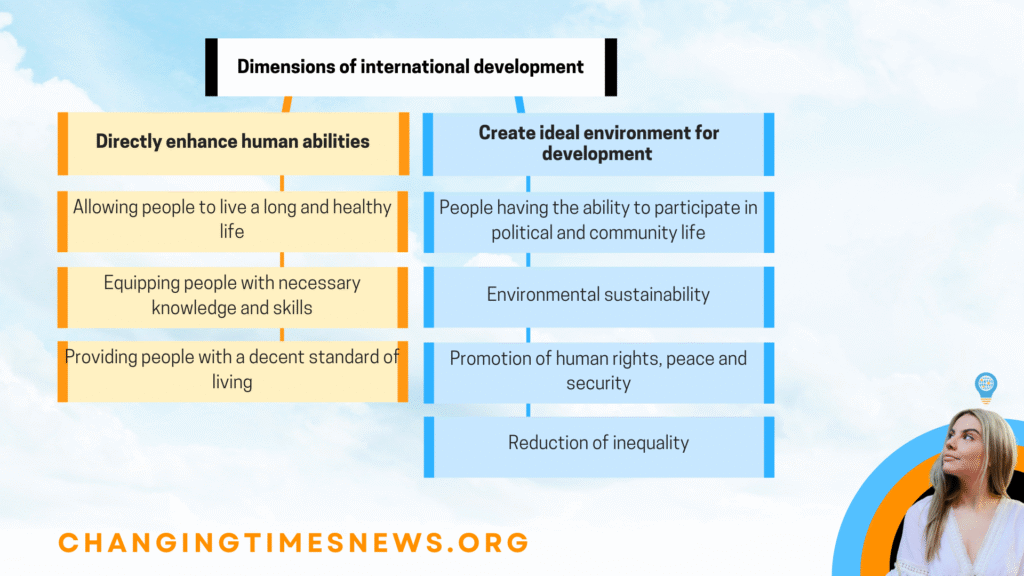

- Development — Longer‐term social and economic progress: enhancing human capabilities, infrastructure, governance; enabling conditions in which communities can thrive.

- Stabilization — Operating mostly in fragile or conflict‐affected settings; roles include restoring governance, political stability, security; acting as the bridge when humanitarian relief must transition toward sustainable systems.

These subsectors overlap, especially in recovery phases. Preparedness (planning ahead, readiness) is presented as the connective tissue: ensuring that when shocks happen, systems can shift more smoothly from crisis response toward durable recovery and transformation.

From Disaster Response to Development

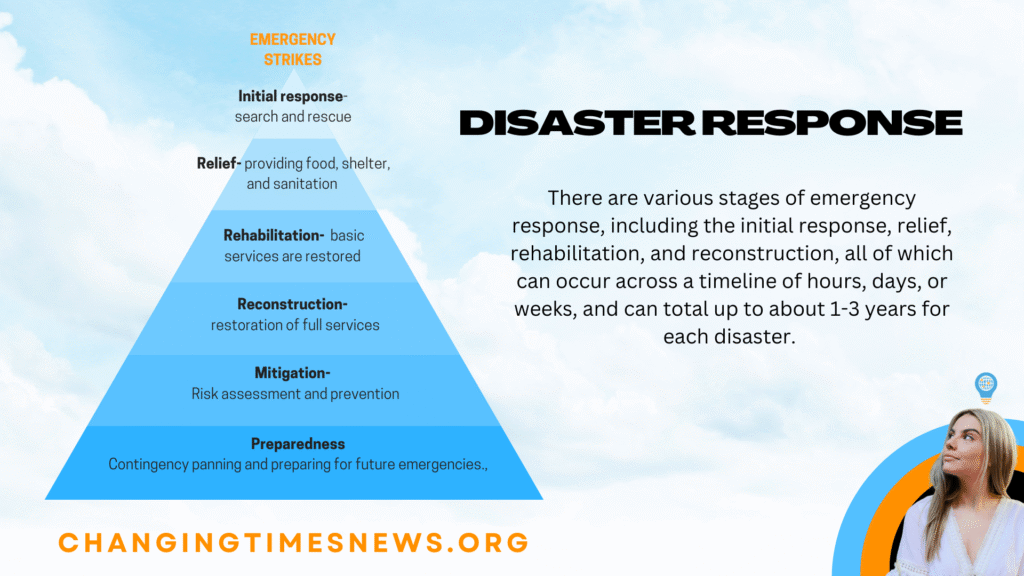

When disaster strikes, the humanitarian sector is the first to mobilize. Search and rescue teams, emergency responders, and medical staff focus on saving lives in the immediate aftermath. Relief then follows, with food, water, shelter, and sanitation provided to stabilize daily survival. Yet humanitarian action is not designed to last indefinitely. As basic services begin to be restored — healthcare facilities reopen, children return to school, clean water systems are reestablished — the emphasis shifts from rehabilitation to reconstruction.

This is where the development sector increasingly takes the lead. Development actors build on the foundation of humanitarian response by working to strengthen systems that prevent communities from slipping back into crisis. That means investing in infrastructure, governance, livelihoods, and education so that people are not only safer in the short term but also more resilient in the long term. In practice, there is no sharp dividing line: mitigation and preparedness work undertaken by humanitarian agencies often overlaps with development programs that address poverty reduction, inequality, and climate adaptation. The shift is therefore less a handoff and more a continuum — one that starts with saving lives and evolves into creating the conditions for lives to flourish.

Why Scale & Resources Matter — And Why They’re Strained

Although humanitarian and development sectors are vast in scope and ambition, the episode notes that financial resources are relatively scarce in spite of scale. To illustrate:

- The United Nations reports that annual investment needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) now runs in the US$4-5 trillion range, significantly up from pre-COVID estimates. United Nations+4DESA Publications+4UN News+4

- Meanwhile, recent trends show funding in the humanitarian space is under pressure. For example, aid appeals are often underfunded; in 2025, the Global Humanitarian Overview requested about US$44.18 billion to assist some 178 million people in 72 countries. ReliefWeb+2OCHA+2

These gaps mean that the transition from relief to recovery, adaptation, and long‐term transformation is often delayed, under‐resourced, or uneven.

Actors & Pathways: Who Does What

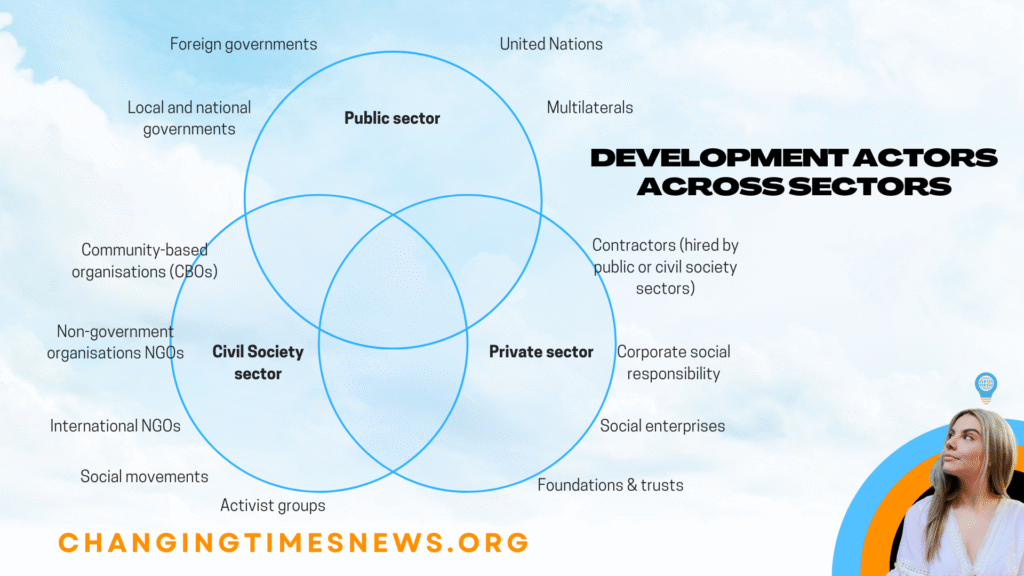

As described in the episode, a wide range of actors are involved:

- Local and national civil society organizations working directly with affected communities.

- International NGOs (e.g., Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders) for scaled interventions.

- Government bodies and intergovernmental agencies, including the U.N., which coordinate policy, funding, and large‐scale action.

- Private sector actors: technological innovation, logistics, financial contributions.

- Different specialists: engineers, logisticians, medical professionals, project managers, policy/advocacy specialists.

Pathways into this work vary: volunteering or internships; technical or professional roles; advocacy and policy work; sometimes crossover between sectors (e.g., humanitarian → development) depending on the setting.

Critical Challenges & Tensions

Some of the tensions illuminated in the episode (and borne out in external reporting) include:

- Resource constraints vs increasing need — climate change, conflict, pandemics all create more frequent or intense shocks.

- Neutrality and impartiality vs political and structural pressures — especially in stabilization, where security/political goals intersect with relief.

- Colonial legacies and power dynamics — the development sector’s history is deeply entangled with colonialism and modernity; efforts to decolonize aid and ensure more equitable, participatory approaches are increasingly central.

- Preparedness and mitigation vs reaction — much more investment is needed upstream (pre‐disaster), but funding often flows only after disasters strike.

What’s at Stake & Why It Matters

Resilience isn’t just a theoretical concept: it determines whether communities merely survive or are able to thrive. The difference between stabilizing and transforming can be generational. Without robust linkages between humanitarian response and development planning, disasters can reset gains, and fragile states can fall into chronic cycles of crisis.

Achieving the SDGs by 2030 depends not just on volume of spending but on how sectors coordinate, how they center affected populations, and how systems are built to anticipate shocks rather than simply respond to them.

As the episode wraps, the key takeaway is that disaster preparedness isn’t an optional aside — it’s central to the architecture of social change. For those considering work in this field, understanding how humanitarian relief, development objectives, stabilization, and systems change interrelate is essential. Skills like technical expertise, project management, policy/advocacy, evaluation, and community engagement are all valuable.