Business is often discussed as though it were a neutral tool—an economic mechanism that can be directed toward good or ill depending on the intentions of those who control it. In contemporary debates about social change, business is increasingly positioned as a solution to complex social and ecological crises, particularly in contexts where governments appear slow, constrained, or politically unwilling to act. Yet this framing risks obscuring a more fundamental reality: business has never existed outside society, nor outside relations of power, value, and moral judgement. It has always been entangled with how societies organise labour, distribute resources, and define responsibility.

The recent Changemaker Q&A episode on business for good invites a more careful and historically grounded examination of this role. Rather than asking whether business can do good in the abstract, the episode asks a more demanding question: under what conditions, and through which models, can business meaningfully contribute to social change—and where are its limits?

Business as a Social Institution, Not Just an Economic Actor

Long before modern capitalism, economic activity was embedded within social relations. In pre-industrial societies, trade and production were closely tied to kinship, religious norms, and communal obligation. Guilds regulated not only quality and pricing, but also apprenticeship, mutual aid, and civic responsibility. Profit existed, but it was constrained by shared expectations about fairness and reciprocity. Business, in this context, functioned as a stabilising social force, albeit one that also limited innovation and mobility.

The Industrial Revolution disrupted this embeddedness. Advances in mechanisation, energy, and transport enabled production at unprecedented scales, transforming business into a dominant driver of urbanisation, class formation, and technological progress. At the same time, the separation of economic activity from social obligation intensified. Efficiency and profit increasingly took precedence over wellbeing, resulting in exploitative labour practices, environmental degradation, and profound social dislocation. Business came to embody a contradiction that remains unresolved today: it generated material prosperity for some while externalising costs onto workers, communities, and ecosystems.

These tensions gave rise to labour movements, regulatory frameworks, and early notions of corporate responsibility. By the mid-twentieth century, particularly in welfare-state contexts, large corporations were understood—at least in part—as social institutions with obligations beyond shareholder returns. Stable employment, collective bargaining, and public infrastructure formed a fragile settlement between business, state, and society.

That settlement, however, proved historically contingent.

Neoliberal Capitalism and the Narrowing of Responsibility

From the late twentieth century onwards, neoliberal reforms fundamentally reshaped the role of business. Market liberalisation, financialisation, and globalised supply chains prioritised shareholder value and short-term financial performance. Social and environmental impacts were increasingly treated as externalities rather than core responsibilities. Importantly, this shift was not driven solely by individual corporate greed, but by structural features of contemporary capitalism: growth imperatives, capital mobility, and power asymmetries between corporations, states, and communities.

Within this context, even well-intentioned businesses face significant constraints. Firms that voluntarily internalise social or environmental costs often struggle to compete against those that do not. Collective problems such as climate change, inequality, and systemic exclusion exceed the capacity of market actors acting alone. And the logic of perpetual growth sits uneasily alongside planetary boundaries and long-term wellbeing.

This does not mean business is irrelevant to social change. It does mean that its role must be understood realistically, rather than romantically.

Why Business Is Still Positioned as a Site of Change

Despite these limits, businesses are increasingly framed as agents of innovation and problem-solving. This reflects not only entrepreneurial capacity, but also the constraints facing governments. Electoral cycles encourage short-termism. Bureaucratic processes slow experimentation. Political risk discourages action on redistributive or contested issues. In many contexts, fiscal austerity and ideological commitments to market solutions have further reduced state capacity.

By contrast, private actors can move quickly, pilot new models, mobilise capital, and scale solutions through existing networks. In areas such as renewable energy, digital services, and community-based delivery, businesses have often acted ahead of regulation rather than in response to it. Climate change offers a particularly stark example: while governments have been slow and fragmented in their responses, many technological and transitional initiatives have emerged from the private sector—often alongside the very practices that created the problem.

This tension sits at the heart of contemporary debates about business for good.

Distinguishing Between Business Models That Engage with Purpose

A key contribution of the episode lies in its careful distinction between different types of purpose-driven business, rather than treating “ethical business” as a catch-all label. Two models, in particular, help clarify what is at stake: B Corporations and social enterprises.

B Corporations represent businesses that seek to be good in how they operate. Certified through a rigorous assessment framework, they commit to defined standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency. Crucially, this commitment is embedded in governance structures, often through amendments to legal constitutions that require directors to consider multiple stakeholders rather than prioritising shareholder value alone. In this sense, B Corps function as a reformist intervention within capitalism, demonstrating that harm reduction, fair treatment, and environmental stewardship can be integrated into mainstream business practice.

Social enterprises, by contrast, exist to do good by design. Their primary purpose is to address a specific social or environmental problem, using commercial activity as the means through which that purpose is sustained. Profits are reinvested to advance the mission rather than maximised for private gain. Historically, social enterprises draw on older traditions of cooperatives, mutual aid societies, and community-owned enterprises, often emerging in contexts where both markets and states have failed to meet essential needs.

Within the social enterprise landscape, multiple models exist: work-integration enterprises that create employment pathways for marginalised groups; redistributive models that channel profits into social programs; community-owned enterprises prioritising local control; service-delivery models operating in spaces of public sector withdrawal; and one-for-one models that link consumption to direct provision. Each reflects a different response to structural gaps in social provision.

What Business for Good Can—and Cannot—Do

Neither B Corps nor social enterprises resolve the deeper contradictions of capitalism. They continue to operate within systems shaped by growth imperatives, competitive pressures, and unequal power relations. Certification does not eliminate extraction, and mission-driven intent does not guarantee scale or sustainability. These critiques are valid and necessary.

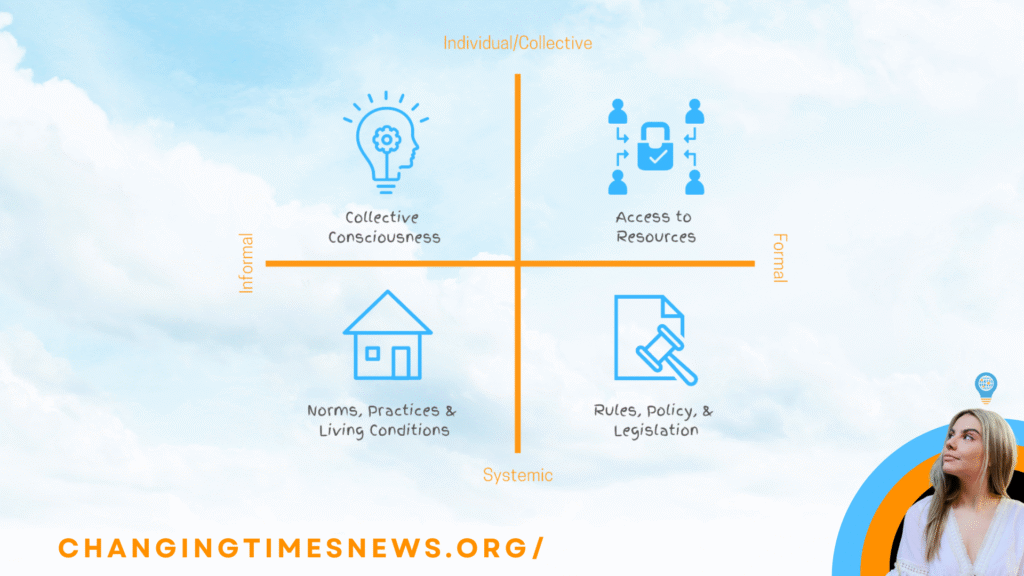

Yet their significance lies elsewhere. They function as sites of institutional experimentation, shifting norms about what businesses are for, who they are accountable to, and how success is measured. They provide concrete mechanisms through which expectations can be reshaped incrementally, rather than relying on abstract ethical claims. For changemakers, they offer practical tools—not total solutions.

Rethinking Business as One Approach Among Many

The central lesson of the episode is not that business should replace other approaches to social change. Activism, policy reform, service delivery, and community organising remain essential. Rather, business must be understood as one approach among many—capable of contributing under certain conditions, constrained under others, and always embedded within wider systems.

Business for good is neither a panacea nor a distraction. It is a contested terrain, shaped by history, power, and structure. Engaging with it requires clarity about purpose, honesty about limits, and a refusal to confuse incremental improvement with transformation.

For changemakers navigating this space, the task is not to idealise business—but to situate it properly within the broader ecology of change.