When we think about social change, research might not be the first thing that comes to mind. Movements are often associated with protests, petitions, or grassroots organizing. But behind many of these efforts lies an often invisible engine: research.

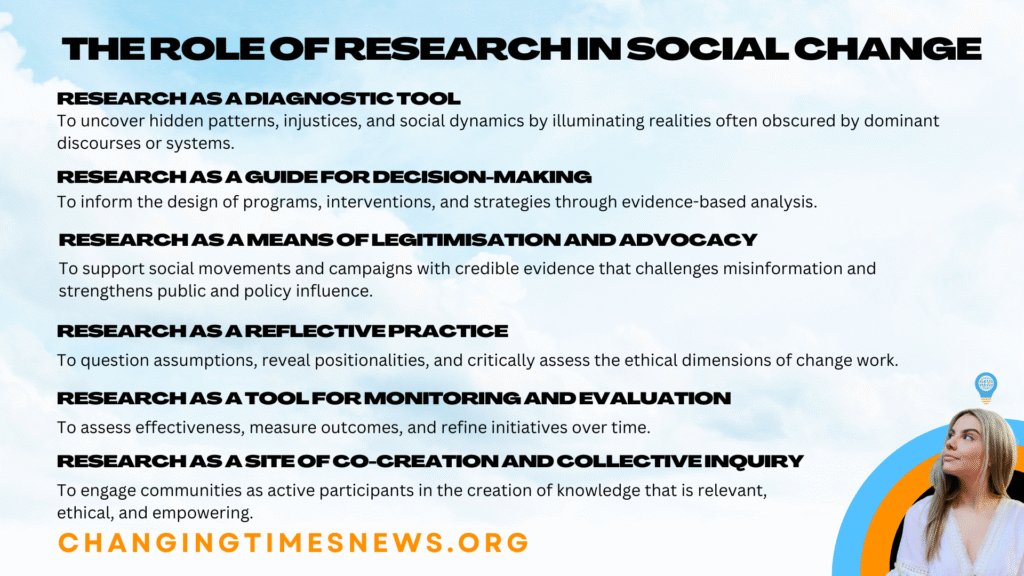

In the latest episode of Changemaker Q&A, I explore the role research plays in activism, policy, and community work—arguing that it is far more than an academic exercise. It is both a diagnostic tool and a compass, guiding strategies, validating claims, and opening doors to transformation.

Making the Invisible Visible

Research can shine a light on issues that dominant narratives keep hidden. “The first way that research is often used to drive social change is as a diagnostic tool,” I explained in the episode, pointing to how data can uncover patterns of inequality and amplify marginalized voices.

Participatory action research is one example, where communities co-produce knowledge rather than being treated as subjects. Globally, movements like #MeToo demonstrated the power of qualitative testimony to reveal systemic injustices, complementing more traditional research methods (UN Women).

From Data to Decision-Making

Research is also central to guiding program design and public policy. Needs assessments, cost–benefit analyses, and feasibility studies help ensure interventions are not based solely on assumptions. For instance, the Melbourne-based social enterprise Street uses data on youth homelessness to design tailored employment pathways for young people.

This evidence-driven approach mirrors broader calls in the nonprofit and development sectors to move beyond anecdotal solutions. According to the OECD, evidence-based decision-making is critical for ensuring aid and social programs are effective and accountable.

Legitimizing Activism

Activism without research risks being dismissed as idealism. Credible studies can lend legitimacy to campaign demands. The Raise the Age campaign in Australia, which pushes to lift the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14, draws heavily on developmental psychology and criminology to argue its case. Similarly, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) synthesizes thousands of studies into reports that serve as the backbone of climate justice movements worldwide (IPCC).

As I noted, “When you are designing an activism campaign… hopefully the demands are not grounded in assumptions, but in fact grounded in research and evidence.”

Research as Reflection

Beyond informing action, research can also challenge harmful methodologies. Decolonial and Indigenous-led approaches emphasize reciprocity and reject extractive knowledge practices. In Australia, the Indigenous Data Sovereignty movement pushes for community control over data and its use, reshaping how evidence is gathered and shared (Maiam nayri Wingara Collective).

This reflects a growing recognition that research is not neutral. All studies carry values, assumptions, and power dynamics—and acknowledging this is essential to producing ethical, socially just knowledge.

Measuring Change

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is another crucial role of research. It helps changemakers understand not just whether their initiatives are producing results, but also whether unintended harms are occurring.

The Ashoka Changemaker Schools network, for example, uses developmental evaluation to adapt strategies in real time, creating flexible feedback loops rather than rigid metrics. This approach reflects a broader shift towards adaptive learning in complex social systems.

Towards Praxis

Ultimately, the transformative potential of research lies in praxis—the integration of theory and practice. As I explained on the podcast:

“The role of research in social change is not just instrumental. The whole point of research is that it should be transformative when it’s rooted in justice.”

That means knowledge must not remain locked in academic journals or reports. It must circulate back to communities, inform strategies, and empower action.

What It Means for Changemakers

For activists, research strengthens campaigns against misinformation. For social entrepreneurs, it informs design and innovation. For policy advocates, it underpins viable alternatives. And for educators, it helps foster critical inquiry.

The challenge is ensuring research is not abstracted away from lived realities. Instead, when practice and theory inform one another, research becomes more than information—it becomes a driver of justice and social transformation.