Social movements rarely grow overnight. More often, they spread conversation by conversation—one seed planted at a time. In the latest episode of Changemaker Q and A, host Tiyana J explores how activists, campaigners, and community organizers can build broader support for their causes using the spectrum of allies framework.

The episode begins with a listener’s question: Can someone without social media still make an impact as a communicator? Tiyana argues that the answer is yes—if we treat conversations as tools for change. “Conversations for change,” she explains, are about planting seeds rather than winning arguments outright. With time and exposure, those seeds may grow into new perspectives and commitments.

Mapping the Spectrum of Allies

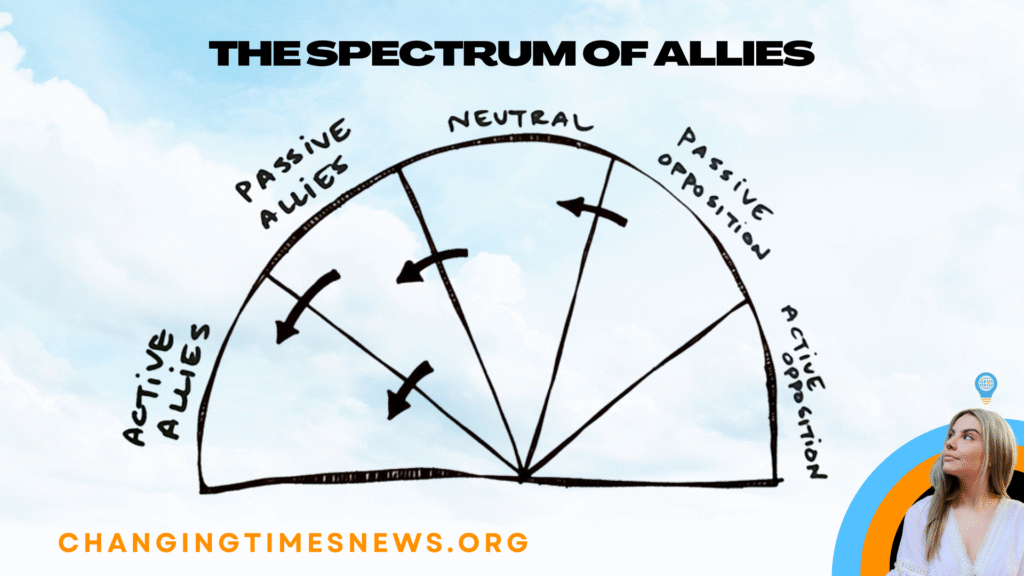

The spectrum of allies is a model used across movements to visualize different levels of support and opposition. Picture a semicircle divided into five categories:

- Active allies – fully engaged supporters, often leading or organizing.

- Passive allies – sympathetic but less involved, perhaps due to capacity limits.

- Neutral – disengaged or uninformed individuals.

- Passive opponents – people who disagree but are not actively resisting.

- Active opponents – those working against the cause.

The framework helps campaigners set realistic goals: not everyone will become an active ally, but small shifts along the spectrum can accumulate into significant change.

Tiyana illustrates this with an example from the U.S. civil rights movement. In 1964, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) launched Freedom Summer, mobilizing northern white college students to support voter registration in Mississippi. Many of these students were already sympathetic but lacked a clear entry point. By inviting them into direct action, SNCC shifted them from passive to active allies—expanding the movement’s reach and influencing their wider social circles.

The Power of Dialogue

The episode emphasizes that shifting attitudes often means engaging empathetically with those who disagree. Rather than confronting opponents with blunt “you’re wrong” statements, activists can use tools like the “explore, equalize, elevate” approach:

- Explore – listen carefully and clarify concerns.

- Equalize – acknowledge the validity of feelings and context.

- Elevate – pose questions that invite deeper reflection.

Research in psychology supports this slow-burn method. Studies on motivational interviewing, for example, show that people are more likely to reconsider beliefs when they feel heard rather than attacked (American Psychological Association).

Patience and Persistence

Movements, Tiyana reminds listeners, require patience. Neutral individuals may need repeated exposure before shifting toward allyship, while opponents may never cross the line. But each conversation adds a “point” in a cumulative game of persuasion.

This incremental approach echoes findings from social change research: long-term shifts in public opinion—on issues from LGBTQ+ rights to environmentalism—tend to result from steady cultural exposure rather than sudden conversions (Pew Research).

In closing, Tiyana frames communication for change as both a practical strategy and a hopeful philosophy: “Every conversation is an opportunity to plant seeds. Not all will sprout—but enough of them, over time, can grow into real transformation.”