When it comes to tackling the world’s biggest challenges—from inequality to climate change—good intentions alone aren’t enough. Social changemakers must also contend with a quieter, less visible obstacle: the way our own brains can trick us.

In a recent episode of the Changemaker Q&A podcast, host Tiyana J explored the role of cognitive biases—the mental shortcuts our brains use to save energy—in shaping how individuals and organizations approach social impact work. Far from being harmless quirks, these biases can cloud judgment, reinforce assumptions, and ultimately limit the effectiveness of campaigns and initiatives.

“Cognitive biases are really important to understand because they don’t just affect individual thought patterns,” says J. “They also show up at larger scales, shaping the way organizations and movements function.”

Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow

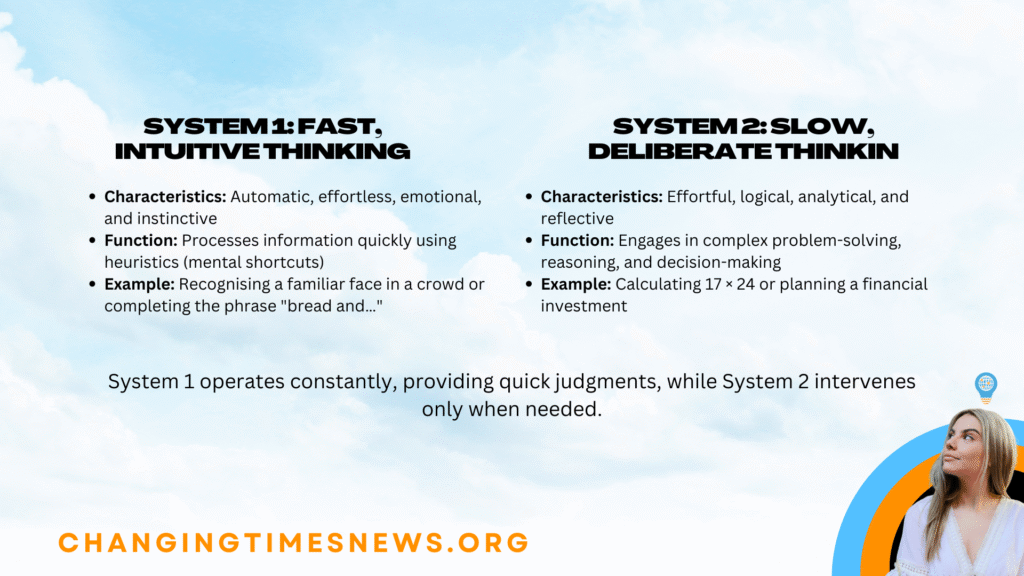

The concept of cognitive bias was popularized by Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman in his seminal book Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011). Kahneman explains that humans rely on two modes of thought:

- System 1, which is fast, intuitive, and emotional.

- System 2, which is slower, more deliberate, and analytical.

Biases tend to emerge from System 1 thinking, where our brains take shortcuts to conserve energy. “Your brain makes up about 25% of your body’s energy use,” J notes in the episode. “So it’s constantly looking for ways to be efficient—even if that efficiency comes at the expense of clarity.”

Common Pitfalls for Changemakers

Several biases are particularly relevant for people working on social change:

- Confirmation bias: The tendency to seek out or favor information that supports existing beliefs. This can create echo chambers in activist circles, limiting understanding of opposing perspectives.

- Availability heuristic: Overestimating the importance of information that’s most immediate or widely publicized. J points to the Australian housing crisis, where sensational headlines about migration often overshadow deeper systemic causes like decades of flawed housing policy.

- Negativity bias: Giving more weight to negative events than positive ones, which can lead to burnout and a sense of hopelessness in social movements. As Hans Rosling argued in Factfulness (2018), the world is often improving in ways we fail to notice because of this bias.

- Status quo bias: Preferring existing systems—even dysfunctional ones—simply because they are familiar. This can stall transformative efforts to move beyond failing economic or political structures.

These aren’t just abstract concepts. They directly shape how changemakers perceive problems, evaluate strategies, and interact with communities. Left unchecked, they can derail campaigns, waste resources, or even reinforce the very systems activists seek to dismantle.

Building Mindful Movements

So what’s the solution? J emphasizes that biases cannot simply be “turned off.” Instead, changemakers must build habits of metacognition—thinking about how they think. Strategies include:

- Pausing before reacting, to allow more rational analysis to catch up with emotional responses.

- Using practices like journaling or mindfulness to spot patterns in thought.

- Intentionally inviting dissent and diverse perspectives into group decision-making to avoid groupthink.

“Sometimes it’s just about adding that second layer of thinking,” J says. “Notice your initial reaction, then step back and ask: what assumptions am I making here? What other perspectives should I consider?”

The Bigger Picture

Understanding cognitive bias isn’t just an academic exercise. It’s a practical tool for anyone working toward social change—whether they’re leading grassroots campaigns, shaping policy, or simply seeking to make more mindful choices in everyday life.

As J reminds listeners, humanity calls itself Homo sapiens—“wise human.” But wisdom, especially in the work of changemaking, requires the humility to recognize where our thinking falls short.