In a world of disputed facts, conflicting narratives, and deep-seated inequality, the idea of “truth” feels as important — and as elusive — as ever. In this episode of Changemaker Q&A, we explore not just what is true, but how something becomes true: the different philosophical lenses through which truth is thought, and a new four-type framework rooted in critical realism that helps changemakers navigate complex social realities.

Classical Theories of Truth: Foundations and Tensions

Philosophers over centuries have wrestled with what “truth” means. Among the major theories:

- Correspondence theory: Truth is a matter of how our statements match or “correspond” with reality. If I say “the grass is green,” this statement is true if there is indeed green grass as described. Critics point out that access to reality is mediated by perception, culture, language — so “matching reality” is not always straightforward.

- Coherence theory: Rather than correspondence with external reality, truth is seen in the consistency and logical integration of ideas within a coherent system. Think of beliefs forming a web: if they all fit together without contradiction, they may be “true” in this sense. The trade-off is that coherence might exist in a closed system that’s disconnected from empirical reality.

- Pragmatic theory: For pragmatists like William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, John Dewey, truth is what works — what bears fruit in practice. If a belief or proposition leads to successful action or solves problems, it is true. Critics argue this can lead to relativism: what “works” can vary by context or power, and usefulness doesn’t always equal accuracy.

- Deflationary or minimalist theories: Philosophers like Alfred Tarski, Quine, or Ramsey propose that truth isn’t a deep, mysterious property but mostly a linguistic or logical device. The word “true” simplifies or supports certain logical operations, but doesn’t itself carry heavy metaphysical weight.

These theories each bring insights and limitations. As your episode argues, social change work often relies on several of them together — we need statements that correspond to facts, coherence among values and beliefs, usefulness in practice, and clarity in how we use language.

Critical Realism & The Intransitive / Transitive Divide

The framework you introduce builds on critical realism, notably developed by Roy Bhaskar. Critical realism emphasizes that there is an objective reality that exists independent of human knowledge (the intransitive dimension), and there is our changing, fallible knowledge/understanding of that reality (the transitive dimension). Critical Realism Network

This distinction helps in thinking about truth: reality doesn’t change because we misunderstand it, but our beliefs about it can evolve, be wrong, be shaped by culture, power, bias.

Four Types of Truth: A Changemaker’s Toolkit

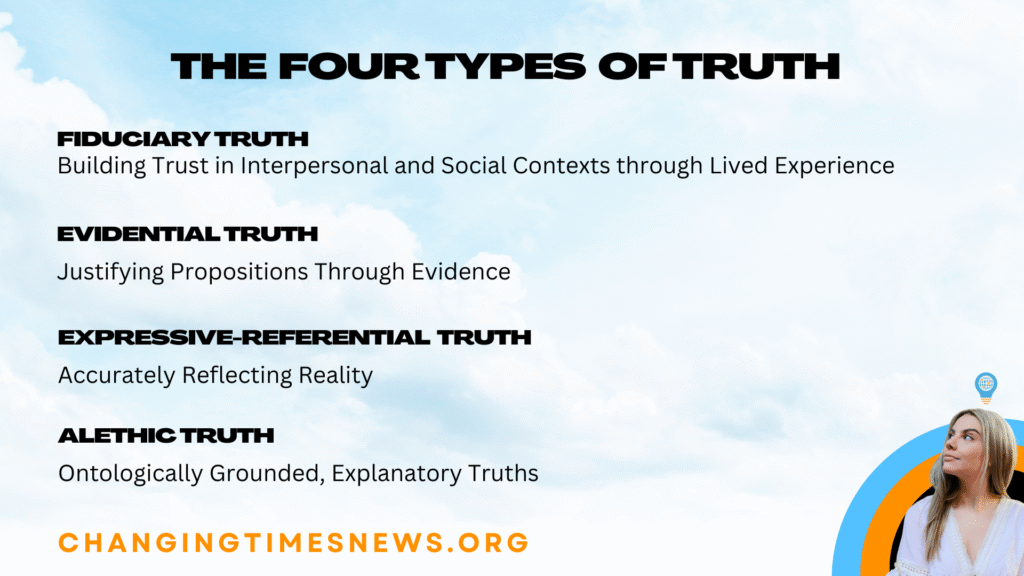

In the podcast, you introduce four types of truth that draw on the above philosophical theories and the critical realist distinction. For those in social change, recognizing these different kinds can be vital for clarity, integrity, and impact.

- Fiduciary truth

This is about trust, relational credibility, and believing lived experience. It’s not just about whether something can be verified; it’s about whether someone’s account, especially someone with experience, is credible and deserving of trust. In changemaking, this is often where justice is made manifest — acknowledging people’s narratives that have been historically silenced. - Evidential truth

Claims justified by evidence: observations, data, research. This is what many policy makers, funders, and academics think of first. It’s essential, but evidence is never neutral; data is collected, interpreted, framed. We need to be wary of whose evidence we privilege and what gets left out. - Expressive referential truth

Here, truth is about how well our language or descriptions reflect reality — especially reality as experienced by people. It combines correspondence (does it match reality?) with the expressive function (does it convey experience, meaning, context?). This matters for representation, storytelling, cultural respect, avoiding tokenism or misrepresentation. - Alethic truth

The deepest layer: seeking the generative, causal, ontological mechanisms that underlie phenomena. Why does something happen? What structures or systems make certain outcomes inevitable (or making change harder)? Understanding alethic truth helps move beyond symptoms to root causes — enabling interventions that are systemic and durable.

Why This Matters in Social Change

Changemakers deal with conflicting truths all the time. Someone’s lived experience may clash with data. Different communities might frame the same event with different expressive referential truths. And without uncovering alethic truths, many solutions remain superficial or temporary.

By recognizing all four kinds:

- We can build more trusting relationships (fiduciary)

- make better grounded decisions (evidential)

- communicate in ways that resonate and don’t mislead or flatten complexity (expressive referential)

- and aim for systemic change rather than Band-Aid fixes (alethic)

For changemakers, truth is not a monolith. It is plural, layered, contested, necessary. The framework you offer doesn’t demand choosing one kind of truth over the others, but knowing when each kind is at play, valuing them properly, and using them together.

Because ultimately, meaningful social change depends not only on what is seen and said, but also on what is believed, trusted, structured, and made real underneath.