When it comes to research, words like “objectivity” and “subjectivity” are often thrown around as if they’re fixed categories. But what if the line isn’t as clear as we assume?

That’s the question tackled in the latest episode of Changemaker Q&A, a podcast hosted by Tiyana J, founder of the Humanitarian Changemakers Network and a PhD student researching communication and social change. The episode explores how subjective ways of knowing can—and must—be taken seriously if we want to better understand the world.

The conversation was sparked by a listener, Des, who asked: “How do you do a PhD in a topic so subjective, as an industrial hygienist? … I can’t imagine researching about a word like empowerment.”

According to Tiyana, the assumption that subjective topics lead to inconclusive or unreliable findings is a misconception. “Inconclusive research findings can result from methodological challenges,” she explains in the episode. Problems like small sample sizes, flawed study design, or data analysis errors affect research in both the natural and social sciences.

Context Matters—But That Doesn’t Make It Subjective

One of the key takeaways from the discussion is that what many dismiss as “subjective” is often better understood as context-dependent. A health intervention or development project may yield results that apply in one community but not another. That doesn’t make the research invalid; it reflects the importance of context in shaping outcomes.

This aligns with broader debates in epistemology—the study of knowledge. Scholars such as Sandra Harding, a philosopher of science, have long argued that all knowledge is produced from a standpoint and that acknowledging context strengthens, rather than weakens, research (Harding, 1992).

Moving Beyond Dualisms

The episode also situates the issue within a wider critique of dualistic thinking—objectivity versus subjectivity, theory versus practice, the natural sciences versus the social sciences. Tiyana highlights how these divisions, rooted in what’s known as Cartesian dualism, continue to shape modern academia.

She draws inspiration from Indian physicist and activist Vandana Shiva, who warns that an overreliance on fragmented knowledge is producing “incomplete human beings.” Shiva’s call for more holistic ways of knowing echoes systems thinking approaches, which emphasize interconnectedness over binary categories (Shiva, 1997).

A Puzzle and an Iceberg

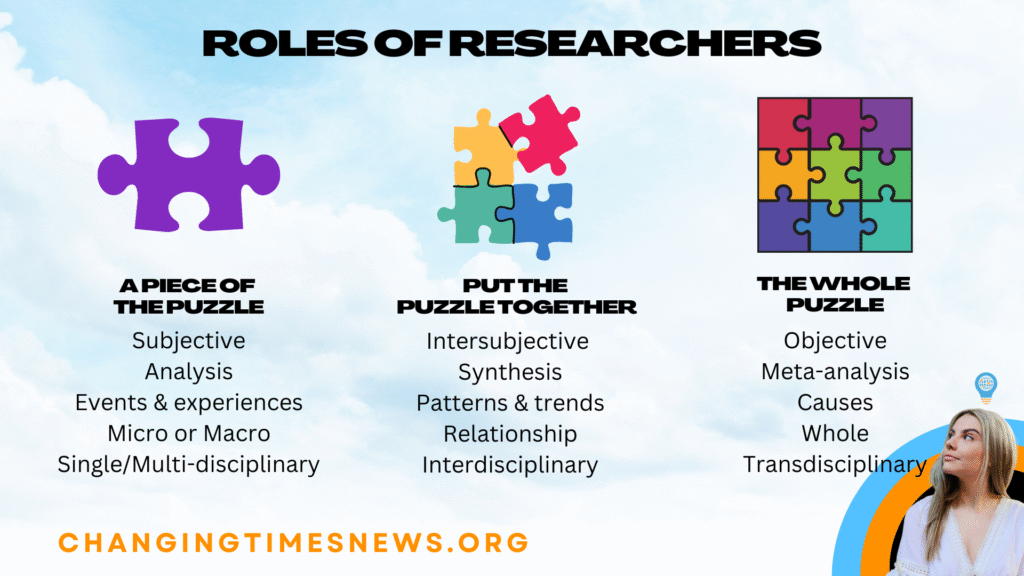

To illustrate, Tiyana introduces two frameworks. First is her puzzle analogy: some researchers focus on a single piece, others connect pieces, and still others step back to see the whole. Each role contributes to building knowledge.

The second is the iceberg model from systems thinking. What we see at the surface—the measurable events or personal experiences—is only a fraction of reality. Beneath lie patterns, structures, and mental models like culture, values, and ideology that shape what happens above.

Applied to her own research on empowerment in rural India, this layered approach allows for both subjective experiences of women and the broader social, political, and cultural structures that influence them.

Knowledge That Evolves

Far from being a weakness, the fact that knowledge can shift, adapt, and respond to context is its strength. As Tiyana concludes in the episode, “The very nature of human knowledge is that it should evolve as humanity evolves.”

For changemakers and researchers alike, embracing both the subjective and the objective—rather than seeing them as opposites—opens the door to more holistic and actionable understandings of complex problems.