What if the key to solving some of the world’s most pressing social challenges lies not in competing for limited resources, but in reimagining what we already have together? That’s the premise behind catalytic thinking, a theory of change developed by social innovator Hilde Gottlieb, and the focus of the latest episode of Changemaker Q&A, the podcast hosted by the Humanitarian Changemakers Network (HCN).

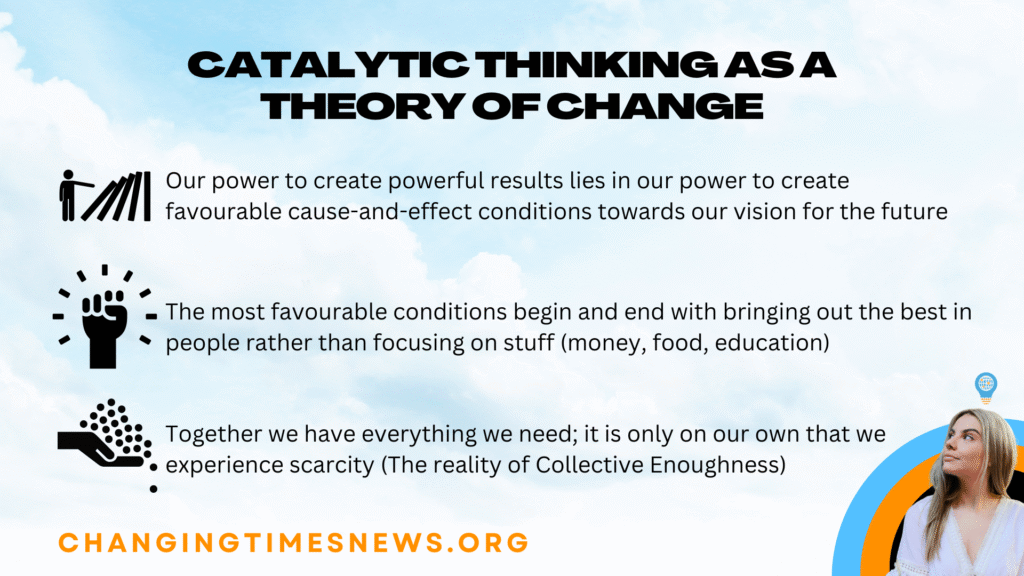

As host, I frame catalytic thinking as a mindset shift: away from scarcity and toward abundance. Much of today’s social change work is stuck in reactive cycles—addressing symptoms rather than root causes. Catalytic thinking offers an alternative, encouraging changemakers to create “favorable cause-and-effect conditions” for the futures they want to see.

Abundance over scarcity

At its heart, catalytic thinking rests on three premises:

- Our power lies in creating the right conditions to bring about the outcomes we envision.

- The most favorable conditions start with people, not things.

- Together we have everything we need.

These ideas align with a growing body of research emphasizing collaboration over competition. For example, the concept of “collective enoughness” echoes Nobel Prize–winning economist Elinor Ostrom’s work on the commons, which showed how communities can sustainably manage shared resources when they focus on cooperation rather than competition (Ostrom, 1990).

Asking better questions

Catalytic thinking is about the questions we ask. Instead of “What’s the problem and how do we fix it?” changemakers might ask: “What is the future we want to create, and what will it take to get there?”

That subtle shift reframes challenges as opportunities. Likewise, instead of worrying “How will we pay for this?” practitioners can ask: “What resources do we have together that none of us has alone?”

Such reframing has parallels in design thinking and positive psychology, where the focus is on assets and possibilities rather than deficits (Stanford d.school, 2022).

Collective solutions and mutual aid

Catalytic thinking also connects to the long tradition of mutual aid. Popularized by Russian thinker Peter Kropotkin in the early 20th century, mutual aid emphasizes cooperation as a survival advantage—a counterpoint to the competitive assumptions of social Darwinism. Practical examples are everywhere: libraries, food banks, tool shares, and even couchsurfing networks.

“Resources are everywhere. Money is scarce. But resources are abundant,” I reflect in the episode, drawing on Gottlieb’s catalytic thinking framework. It’s a challenging idea in a world shaped by capitalism and competition. Yet it offers a hopeful vision: one where scarcity dissolves when people act together.

As Hilde Gottlieb herself has written, “When we change the way we see things, things change” (Creating the Future, 2023).

For changemakers seeking new strategies, catalytic thinking may not just be a theory. It could be the catalyst for reimagining how social change itself is made.