From “ethical fashion” labels to debates about responsible AI, the word ethical is everywhere. But what does it really mean to call something ethical — and how should changemakers navigate the dilemmas that come with it?

In the latest episode of Changemaker Q&A, host and Humanitarian Changemakers Network founder Tiyana J draws on her background in philosophy to unpack this question, posed by listener Courtney: “Whether or not something is ethical tends to be quite subjective. How should we assess whether something is ethical?”

Her answer reveals why this seemingly simple question has occupied philosophers for centuries — and why it matters deeply for anyone working in social change today.

Subjective or Objective? The Metaethical Debate

The first step, Tiyana explains, is to look beneath the question itself. Metaethics — the study of the foundations of morality — asks whether morality is inherently subjective or whether universal moral truths exist.

- Moral relativism argues that ethics depend on culture, context, or personal belief. What one society sees as right, another may condemn. Abortion, for instance, remains morally acceptable in some countries and deeply contested in others. Relativism emphasizes tolerance and respect for diverse worldviews.

- Moral realism, by contrast, insists that some moral facts exist independent of opinion. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted in 1948, embodies this perspective by asserting principles — such as the right to life, dignity, and freedom from torture — as universally binding.

Tiyana’s own stance lies in between: “There are universal moral truths that pertain to human flourishing,” she says, “but the way they are actualized depends on context.” A right to education, for example, might look very different in rural Serbia than in urban Brisbane, yet both fulfill the same universal principle.

Two Paths: Consequences vs. Duties

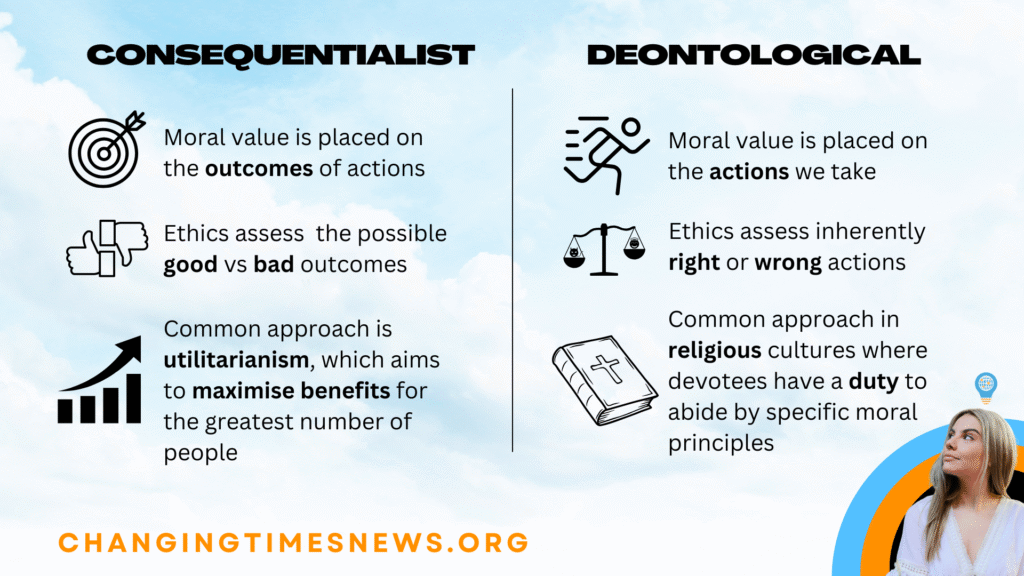

From there, Tiyana moves into normative ethics — the frameworks we use to evaluate whether actions are good or bad. Two of the most influential traditions dominate:

- Consequentialism, which judges actions by their outcomes. The best-known form, utilitarianism, seeks the “greatest good for the greatest number.” Philosopher Peter Singer’s work The Life You Can Save popularized this approach, urging people to donate to charities that save the most lives per dollar. For Singer, the choice between buying new shoes and saving a drowning child illustrates our moral duty to act when the stakes are clear.

- Deontology, which instead evaluates the inherent rightness or wrongness of actions. Rooted in the work of Immanuel Kant, it emphasizes duty and universal principles. Organizations like the Red Cross embody this approach, adhering strictly to principles such as neutrality, impartiality, and humanity — even when outcomes are uncertain.

Both frameworks have strengths and weaknesses. Consequentialism can overlook minority needs or long-term impacts in favor of majority happiness. Deontology can ignore harmful outcomes in the name of duty. “The strongest ethical choices,” Tiyana argues, “are those that consider both actions and outcomes.”

Putting Ethics Into Practice

This brings us to applied ethics — how theory plays out in everyday dilemmas. For changemakers, this means blending principles with practicality. Tiyana offers several tools:

- Frameworks and principles: Rely on guiding documents like the UDHR, or adopt personal values such as fairness, honesty, and environmental sustainability.

- Transparency and accountability: Look for companies and organizations with clear reporting, certifications like B Corp, or fair-trade and sustainability labels.

- Expertise and lived experience: Listen not only to specialists but also to those directly affected by an issue.

- Intuition: Don’t dismiss gut feelings. Moral instincts can be valuable guides, even when reasoning isn’t fully formed.

- Critical reflection: Develop the habit of weighing both deontological and consequentialist perspectives when making tough calls.

Why It Matters

The proliferation of “ethical” branding — from fashion to finance — shows how the term risks being watered down. Without careful reflection, it can become a marketing buzzword rather than a meaningful commitment.

For changemakers, though, ethics cannot be an afterthought. Whether designing policy, leading protests, or donating money, ethical frameworks shape decisions with real consequences for people and the planet.

As Tiyana reminds her listeners, “There is no one-size-fits-all approach to ethics. But the more fluent we become in these frameworks, the more we can navigate dilemmas with confidence, humility, and care.”

In a world where the meaning of “ethical” is hotly contested, perhaps the most ethical act of all is to keep asking — and keep reflecting.