When people talk about building a “new economy”, the conversation often moves quickly to things that feel concrete: different business models, new metrics beyond GDP, localised production, or rethinking work and consumption. All of that matters. Yet Peter Tait’s argument is more foundational, and in some ways more confronting.

If the rules of public life are not working, then even the best economic ideas will struggle to take root. If decision-making systems are routinely overridden by concentrated commercial power, then the economy will keep reproducing outcomes that damage human wellbeing and planetary health. In this framing, the pathway to a new economy runs directly through governance.

Not as a niche political interest. As the operating system.

Peter is a practising GP who works in mental health and alcohol and other drug care, and teaches population health at ANU. Over decades of engagement in public health, peace, social justice, and climate issues, he came to a common conclusion: many of these crises persist not because people lack good ideas, but because the decision-making system consistently fails to deliver the public good. That recognition led him to convene the Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy (CAPAD), a civil society initiative focused on strengthening democratic participation and pushing for “good governance”.

This episode offers a clear proposition: if we want an economy that supports wellbeing without “blowing up planetary health”, then governance is not peripheral. It is central.

What governance is — and why it matters

In everyday language, governance is often treated as synonymous with “government”. Peter distinguishes the two.

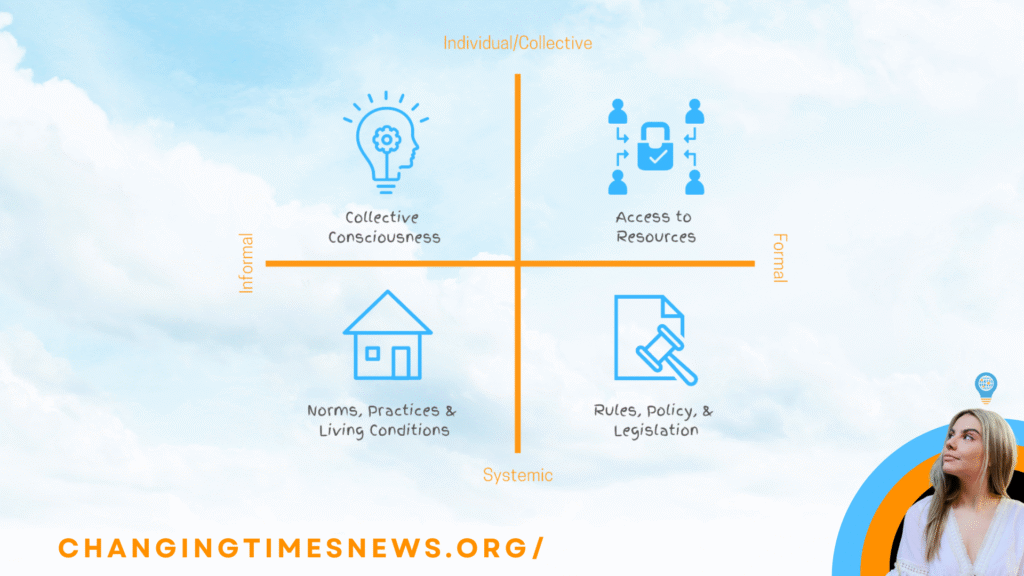

Governance is the process or system communities use to make decisions about what they will do for themselves and for others. Government is one institutional form that governance can take, particularly at nation-state, state/territory, and local council levels. But governance also happens in organisations, workplaces, community groups, and even families. It is present anywhere a group must decide what matters, what to prioritise, and how to act.

That might sound abstract. It becomes concrete very quickly once you notice what governance decisions actually do.

They decide how resources are allocated. They set the rules that shape markets. They determine whether public services are funded and accessible, whether ecosystems are protected, and whether the costs of harm are absorbed by communities while benefits flow elsewhere. In this sense, the “economy” is not a separate entity floating above society. It is an outcome of governance choices.

Peter’s claim is simple: good governance delivers for people and the planet. Bad governance does not.

From campaigning to changing the system

Many listeners will be familiar with the exhaustion that can come from advocacy work: decades of campaigning, incremental wins, and then an overall trajectory that still points in the wrong direction. Peter describes a realisation that was gradually consolidating through the early 2000s: civil society groups can win battles, but still lose the broader war.

Why? Because the playing field is uneven.

In Peter’s account, corporations and commercial entities are able to use their influence to override or subvert ecological and public interests. Civil society often lacks equivalent power. This does not mean advocacy is futile. It means advocacy has limits when the deeper system of governance does not reliably translate public priorities into policy and action.

That is where CAPAD positions its work: not only trying to influence decisions, but helping to change how decisions get made — and who has leverage inside that process.

This becomes a shift in strategy. Instead of treating politics as an obstacle to “get around”, the challenge is to treat governance as something to work with, reform, and redesign. Not as a distant spectacle. As a domain of practice.

Beyond voting: participation as a civic responsibility

Australia’s political culture tends to frame democratic participation narrowly. You vote every few years. You might write to your MP when something goes wrong. Then you return to private life.

Peter argues that this model leaves too much power concentrated in places that are not accountable to the people most affected by decisions. It also narrows the meaning of citizenship to periodic compliance rather than ongoing participation.

His alternative begins with a different expectation: elected representatives should not merely be elected and left alone. They should face ongoing, organised, collective accountability from their communities. Peter’s language for this — borrowed from a colleague — is memorable: the “hot breath of democracy”. It points to a practical mechanism of power, not a moral aspiration.

When MPs know their constituents are paying attention between elections, and when that attention is coordinated rather than isolated, they have to factor it into decision-making alongside party pressures and donor influence. That shift is small, but it can be consequential. It changes the incentive landscape.

Peter is careful to acknowledge reality. People are busy. They have work, care responsibilities, health needs, and limited time. The point is not that everyone must become a political organiser. It is that citizenship involves some shared responsibility to keep democratic systems responsive. Participation can be scaled. It can be occasional. It can be collective.

But it must exist.

Two pathways: pressure within the system and alternatives beside it

Peter outlines two broad pathways for improving governance.

The first is to make parliaments and MPs actively work for good governance by creating electorate-level mechanisms that apply pressure and create accountability. This involves community groups that meet, identify shared priorities, and engage MPs consistently. It also involves candidate forums during election cycles, where candidates are asked clear questions about how they will support good governance and participatory decision-making.

This approach is related to the community independence movement — the “choose your own and send them to Parliament” strategy — but Peter’s focus also includes working with the MP you already have. If they are elected to represent the community, then a community can organise to ensure they do.

The second pathway is to build local alternative community governance arrangements. This is where direct democratic practice becomes a lived experiment, not merely a policy proposal. Communities can develop decision-making structures that coordinate action, allocate resources, and build shared capacity even when governments are not acting at the scale required.

These pathways are not mutually exclusive. In Peter’s framing, we need them all.

What direct democracy can look like in practice

One of the barriers to participatory democracy is a common misconception: that it means endless meetings and total consensus on everything. Peter argues this is a misunderstanding of how participation can be structured.

Many decisions are routine once policies are set. Others can be delegated to skilled public servants within clear accountability frameworks. Participation is most needed for setting the rules, making high-stakes or contested decisions, and evaluating whether systems are delivering outcomes.

This is where models like sociocracy and other circle-based governance approaches become relevant. Peter describes how direct democracy can work effectively in small groups, particularly when facilitation and training are in place. To scale beyond small groups, a “nested” structure can be used: small circles deliberate and decide, then send delegates to higher-level circles, and information and resources flow back down. This enables coordination without centralising all power.

A crucial distinction Peter makes is between consensus and consent. Consensus can mean talking until everyone agrees, which can stall. Consent-based models allow groups to move forward if there are no reasoned objections, while creating pathways for people to stand aside or opt out without blocking collective action. It is a form of governance designed for pluralism.

This matters for new economy work. Cooperative, network-based, place-based initiatives often fail not because people lack commitment, but because decision-making becomes unclear, exhausting, or conflictual. Governance design becomes a practical capacity, not an abstract ideal.

Deliberative democracy: citizens’ assemblies and juries

Peter also points to deliberative democracy as a growing domain of practice. Citizens’ juries and citizens’ assemblies bring together randomly selected community members (through a process called sortition), provide them with evidence and expert input, and support structured discussion leading to recommendations.

These processes are not a replacement for all democratic decision-making, but they can strengthen legitimacy, broaden participation beyond the “usual suspects”, and create more thoughtful policy proposals.

Peter references examples such as standing citizens’ assemblies in parts of Europe, and local deliberative experiments where communities generate recommendations for elected representatives to take into parliament. The underlying logic is consistent: if decisions affect the public, the public should be meaningfully involved in making them.

The economy as a set of choices, not a force of nature

A recurring theme in the episode is a reframing of the economy. Peter draws on an idea often associated with public economists: the economy is not a thing that exists independently. It is a system for allocating resources, distributing benefits, and assigning costs.

Once you accept that, “economic” outcomes become political outcomes. Not partisan politics, necessarily. Governance politics. Who decides? With what accountability? In whose interests? Under what rules?

This is why democracy is not separate from the new economy conversation. It is the method through which economic priorities are set and enforced.

Without improved governance, the new economy risks remaining a collection of inspiring marginal projects, constantly vulnerable to the dominant system’s ability to extract value, rewrite rules, and concentrate decision-making power.

A practical first step: join or build democratic infrastructure

Peter’s most pragmatic recommendation is also the most straightforward: join groups already doing this work, and learn from their practice. Start where you are. Participate at a level that is sustainable. Build relationships and capacity over time.

This is important. In social change spaces, there is often a tendency to treat governance as either too big to touch or too technical to enter. Peter’s approach treats it as a field of civic infrastructure. Like community energy, local food systems, or mutual aid networks, democratic participation can be built deliberately. It requires skill. It requires patience. It requires facilitation.

It also requires a cultural shift: from democracy as a periodic ritual, to democracy as an ongoing practice.

Why this matters now

Peter’s argument is not that every person must become a governance expert. It is that the conditions for a new economy depend on the quality of governance. And the quality of governance depends on whether people are organised enough to hold decision-makers accountable and to build credible democratic alternatives beside existing institutions.

This is not fast work. It is not glamorous. It is often frustrating.

It is also, in Peter’s framing, one of the most strategic things civil society can do if it wants to stop losing the broader war for wellbeing and planetary health.

The new economy conversation, then, is not only about what we want. It is about how we decide.

And whether the people most affected by decisions can reclaim the power to make them.