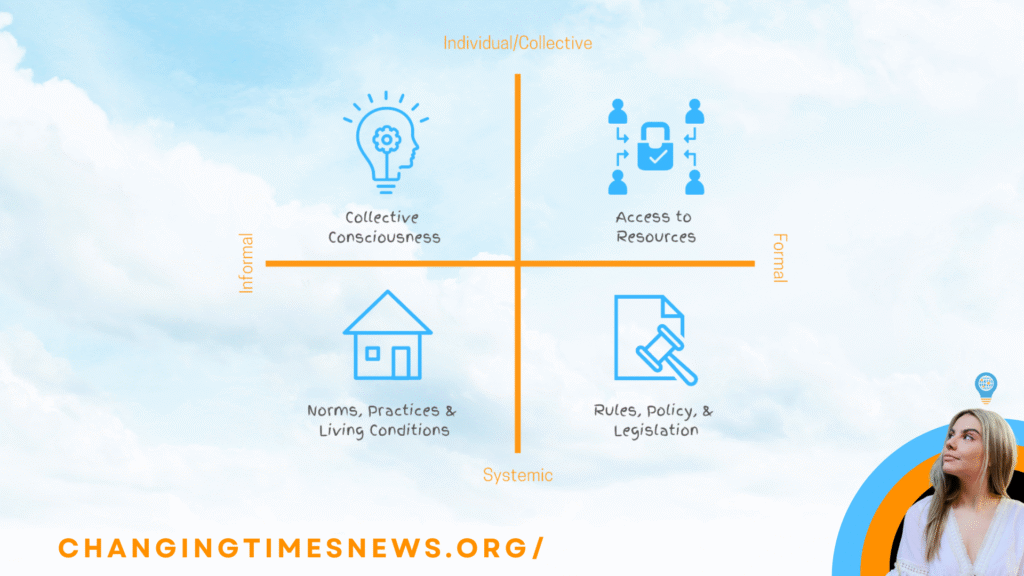

When people talk about building a new economy, the conversation often starts with the visible structures: money, markets, jobs, housing, energy, and policy. These are important. They shape daily life in immediate ways. Yet beneath them sits something quieter and more foundational: how we learn what the world is, what we value, and what counts as “common sense”.

In a recent episode of Voices of the New Economy, Dr Elizabeth McDougal — a lecturer in Contemplative Pedagogy and Applied Buddhist Studies at Nan Tien Institute — makes a compelling case that education is not an “add-on” to economic transition. It is one of its cruxes. If we want regenerative futures, we also need what she describes as epistemological rewiring: a shift in our ways of knowing, learning, and becoming.

This is not a call for minor curriculum reform. It is an invitation to rethink the relationship between knowledge, culture, and economy itself.

The economy is a learning system

One of the most accessible ways to grasp Elizabeth’s argument is to see the economy as a learning system. Economies are not only made of transactions and institutions. They are held together by habits, expectations, and shared stories about what matters. Those habits and stories are learned.

Modern schooling and higher education have played a major role in reproducing the cultural conditions that growth-oriented economies require. Not only by teaching skills for employment, but by cultivating dispositions that fit the system: segmented time, standardisation, competition, productivity, and the idea that success is measured by outputs that can be compared.

This is why the phrase “the economy is embedded in daily life” matters. It is not only embedded in what we buy or how we work. It is embedded in how we are trained to think, to interpret worth, and to relate to uncertainty. Education helps produce economic subjects.

To change the economy, then, is also to change the cultural learning practices that keep it stable.

Beyond cognitive-centric intelligence

A key critique Elizabeth offers is that mainstream education tends to privilege cognitive-centric models of intelligence. In practice, this often means that learning is framed as primarily intellectual, abstract, and measurable. Knowledge becomes something that can be accumulated, tested, credentialed, and converted into advantage.

This approach has consequences. It sidelines other intelligences that matter for both human wellbeing and ecological survival: relational intelligence, emotional maturity, embodied awareness, imagination, and the capacity to listen. It can also narrow what students believe their own strengths are, leaving many people with the sense that they are “not smart” simply because their intelligence does not fit a narrow metric.

Elizabeth’s point is not anti-intellectual. It is integrative. Her argument is that when education is disconnected from the body, from lived experience, and from relational practice, it produces a distorted form of intelligence — one that can become highly skilled at extraction without developing equivalent capacities for care, restraint, or ethical discernment.

This is where the new economy conversation deepens. Extraction is not only a material logic. It is also a way of knowing.

Contemplative pedagogy as whole-person cultivation

Elizabeth’s work draws on contemplative pedagogy, an approach to learning that emphasises awareness, reflexivity, and whole-person cultivation. In simple terms, pedagogy refers to how we teach and learn. Not just what the content is, but what methods and values shape the learning environment.

Contemplative pedagogy is not simply “mindfulness in the classroom”. It is broader, and in some forms, more radical. It invites a shift from learning as the transfer of certainties to learning as cultivation: cultivating attention, discernment, the ability to hold complexity, and the ability to learn with others rather than merely alongside them.

This matters because many of the challenges we face now — climate instability, misinformation, social fragmentation, and political polarisation — are not problems that can be solved by technical knowledge alone. They require capacities that are ethical, relational, and self-aware. They require people who can slow down their reactions, listen, and revise their assumptions.

In this sense, education becomes less about producing compliant workers and more about cultivating mature humans.

Why slowing down is not a luxury

In the episode, the theme of slowing down appears repeatedly. Not as a wellness trend. As a political and cultural act.

Elizabeth argues that modern life often pushes people into fast cognition, constant stimulation, and an overstretched nervous system. In that state, it becomes harder to think critically, harder to feel, and harder to relate. This has implications for our collective capacity to respond to crisis. If people are chronically exhausted and disconnected from their own bodies, their ability to engage with complexity and sustain long-term action diminishes.

Slowing down, in this framing, is not retreat. It is creating the conditions for clearer perception and wiser response. It is also a way of shifting what is valued. Time itself becomes a form of wealth. Being together becomes a measure of prosperity.

This is a profoundly economic proposition, even though it does not look like one at first glance.

Play, ritual, and learning through uncertainty

One of the most practical parts of the conversation is Elizabeth’s reflection on play and ritual as underappreciated learning practices. Both are ways of relating to uncertainty without becoming overwhelmed by it.

Play allows experimentation. It makes learning adaptive rather than rigid. It creates a space where mistakes are part of the process, not evidence of failure. In a world changing rapidly, the capacity to learn through experimentation becomes essential.

Ritual, in contrast, creates shared meaning. It helps communities name what matters, process collective emotions, and return to values that might otherwise be eroded by speed and stress. This is particularly relevant in movements for climate justice and systems change, where grief, fear, and fatigue are common. When these emotions are processed individually, they can become paralysing. When they are held collectively, they can become connective.

This echoes the insight that a new economy is also an emotional and cultural transition. People need practices that help them remain human while navigating upheaval.

Education as the crux of emerging economies of care

Elizabeth’s central claim is that regenerative economies require epistemological rewiring. In other words, the transition is not only about changing what we do. It is about changing how we know.

That involves moving beyond a narrow model of intelligence, reclaiming learning as whole-person cultivation, and creating spaces where relational and ethical capacities are strengthened. It also means recognising that education is not restricted to schools and universities. It happens in parenting, organising, community projects, workplaces, and everyday life. Every setting that transmits values is pedagogical.

If that is true, then the question becomes less “how do we design the perfect alternative economy?” and more “how do we learn to live differently — together?”

This is where the idea of emergence becomes useful. Whatever comes after the current system is unlikely to arrive as a fully designed replacement. It will emerge from the values, practices, and relationships being cultivated now. The seeds we plant are pedagogical as much as they are political.

A starting point that is both simple and demanding

Elizabeth does not offer a quick program. She offers an orientation. It begins with slowing down enough to notice what is happening within and around us. It involves attention. Presence. Honest reflection. The willingness to learn again.

These are not small things. They are the foundations of any serious transition.

If new economies are to be more than marginal experiments, they will require new forms of knowledge transmission that can scale without becoming extractive. They will need communities capable of discernment, complexity, and care.

And that work starts with learning. Not just what to think, but how to be.